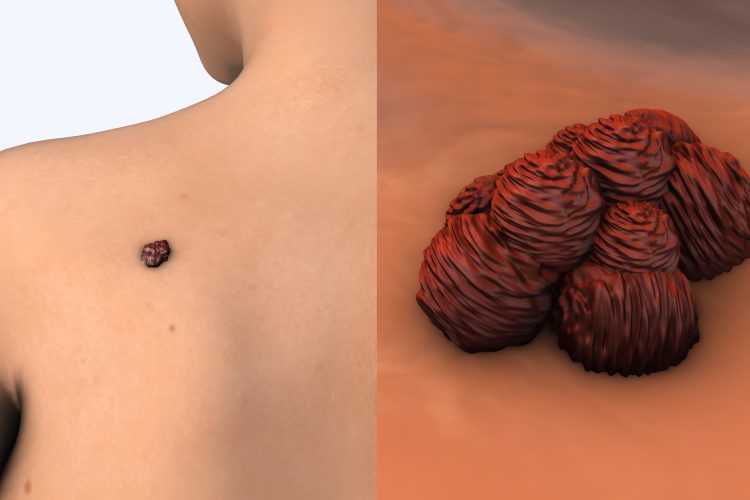

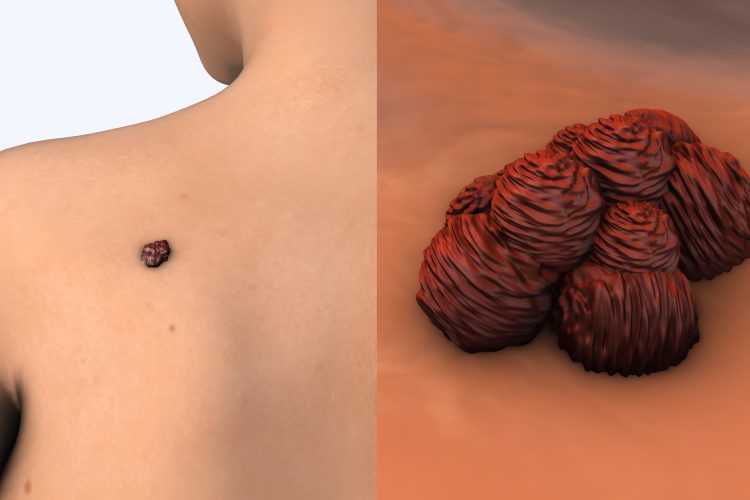

Protein FSP1 found to help melanoma survive in lymph nodes

Posted: 6 November 2025 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

New research has discovered a key survival mechanism in metastatic melanoma, revealing that cancer cells spreading to lymph nodes depend on a protein called FSP1 to avoid cell death.

Scientists at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health have identified a crucial protein that helps metastatic melanoma cells survive after spreading to lymph nodes – which could help to develop a new class of cancer therapies.

According to the study, melanoma cells that metastasise to lymph nodes depend on a protein known as ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) to stay alive. By targeting this protein, researchers say it may be possible to slow the progression of the disease.

Unlocking a survival mechanism

Ferroptosis is a type of cell death caused by the build-up of oxidised fats within cell membranes. When this oxidation becomes excessive, the cell’s structure collapses and it dies. Many cancer cells rely on antioxidant defences such as FSP1 to prevent this destructive process.

Automation now plays a central role in discovery. From self-driving laboratories to real-time bioprocessing

This report explores how data-driven systems improve reproducibility, speed decisions and make scale achievable across research and development.

Inside the report:

- Advance discovery through miniaturised, high-throughput and animal-free systems

- Integrate AI, robotics and analytics to speed decision-making

- Streamline cell therapy and bioprocess QC for scale and compliance

- And more!

This report unlocks perspectives that show how automation is changing the scale and quality of discovery. The result is faster insight, stronger data and better science – access your free copy today

Our study shows that melanoma cells in lymph nodes become dependent on FSP1 to survive, and that it is possible to decrease melanoma cell survival in lymph nodes with novel FSP1 inhibitors.

“Our study shows that melanoma cells in lymph nodes become dependent on FSP1 to survive, and that it is possible to decrease melanoma cell survival in lymph nodes with novel FSP1 inhibitors,” said corresponding author Jessalyn Ubellacker, Assistant Professor of Molecular Metabolism. “These findings lay the foundation for potential new therapeutic strategies aimed at slowing cancer progression by targeting ferroptosis defence mechanisms.”

While previous research on ferroptosis has largely focused on experiments in vitro, this study examined how the tumour’s natural environment inside the body influences its defences.

Tumour growth reduced in mice

To test their hypothesis, the researchers studied melanoma cells that had spread to the lymph nodes of mice. They then delivered experimental FSP1 inhibitors directly to the tumours.

Within the lymph nodes, FSP1 acted as a vital shield against cell death. When the protein was blocked, tumour growth dropped sharply. However, when the same drugs were tested on melanoma cells in laboratory culture, they saw little effect – a finding that underlined the importance of studying cancer in vivo.

The researchers believe this environment-specific dependency could be key to developing more effective, targeted treatments.

Rethinking how cancer survives

Beyond its therapeutic implications, the study improves our understanding of ferroptosis in cancer. Rather than being a uniform process, the susceptibility of cancer cells to ferroptosis appears to vary depending on the tissue environment in which they grow.

Rather than being a uniform process, the susceptibility of cancer cells to ferroptosis appears to vary depending on the tissue environment in which they grow.

“Metastatic disease, not the primary tumour, is what kills most cancer patients. Yet little is understood about how cancer cells adapt to survive in organs such as lymph nodes,” said first author Mario Palma, postdoctoral research fellow in the Ubellacker Lab. “We discovered that niche features of the lymph node actively shape which antioxidant systems melanoma can use. That context-specific dependency had not yet been fully appreciated and suggests that, rather than trying to kill every tumour cell the same way, we can exploit the weaknesses that arise as cancer spreads.”

A broader therapeutic target

A similar study from the Papagiannakopoulus Laboratory at New York University reported that blocking FSP1 in lung cancer cells also triggered ferroptosis and reduced tumour growth.

Together, the two studies bolster the case for FSP1 as the next key therapeutic target across multiple cancer types – helping the fight against metastasis, the deadliest aspect of cancer.

Related topics

Animal Models, Cancer research, Drug Discovery, Drug Targets, In Vivo, Oncology, Therapeutics, Translational Science

Related conditions

Metastatic melanoma

Related organisations

New York University, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health