Study suggests how to develop intranasal vaccines for COVID-19 and flu

Posted: 30 August 2021 | Anna Begley (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

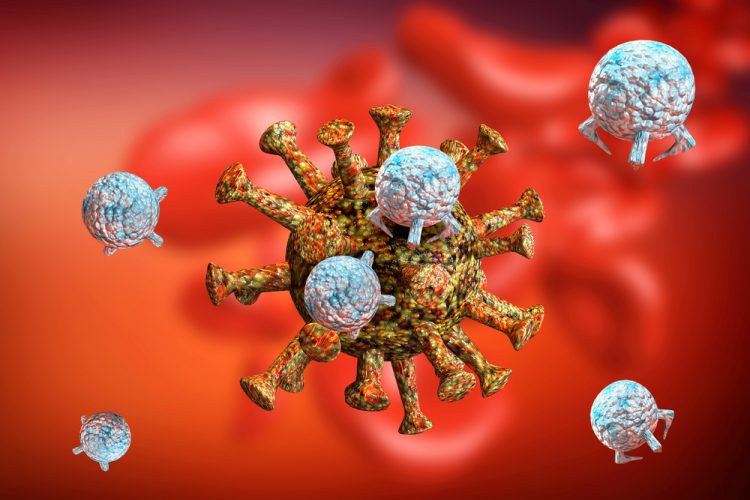

New research has explored the role of nasal bacteria to better develop intranasal vaccines for viruses such as COVID-19 and flu.

A team at the University of Tokyo, Japan, have been investigating the critical role of nasal bacteria to provide clues on developing more effective intranasal vaccines for COVID-19 and flu. The team hope that their research will lead to the production of such vaccines in the near future.

While gut microbiota play a critical role in the induction of adaptive immune responses to influenza virus infection, the role of nasal bacteria in the induction of virus-specific adaptive immunity is less clear. The team, led by Dr Takeshi Ichniohe, therefore wanted to determine the effects of nasal bacteria in the induction of mucosal immune responses to influenza virus infection. They began by treating mice intranasally with an antibiotic cocktail to kill the nasal bacteria before influenza virus infection.

The researchers found that disruption of nasal bacteria by antibiotics before influenza virus infection enhanced the virus-specific antibody responses. “We found that intranasal application of antibiotics (to kill nasal bacteria) could release bacterial pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP), which are bacterial components that stimulate innate immunity that act as mucosal adjuvants for influenza virus-specific antibodies response,” Ichniohe expanded.

The study also showed that while the upper respiratory tract contained commensal bacteria, relative amounts of culturable commensal bacteria in nasal mucosal surface were significantly lower than that in the oral cavity. The researchers tested whether intranasal supplementation of cultured oral bacteria enhances antibody responses to intranasally administered vaccine and found that oral bacteria combined with intranasal vaccine increased antibody responses to intranasally administered vaccine.

“Our study shows that both integrity and amounts of nasal bacteria may be critical for effective intranasal vaccine,” concluded Ichinohe. “We showed that oral bacteria-combined intranasal vaccine protects from influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

Ichniohe added that the findings provide clues to developing better intranasal vaccines. “We wish to develop effective intranasal vaccines for influenza and COVID-19 in the near future,” he stated.

The study was published in mBio.

Related topics

Antibiotics, Antibodies, Drug Delivery, Drug Targets, Immunology, In Vivo, Molecular Biology, Vaccine

Related conditions

Covid-19

Related organisations

University of Tokyo

Related people

Dr Takeshi Ichniohe