Cells regenerate liver without cancer risk

Posted: 17 August 2015 | Victoria White

Researchers supported by the NIH have discovered a type of cell, known as hybrid hepatocytes, essential to regeneration of the liver…

Researchers supported by the US National Institute of Health (NIH) have discovered a type of cell in mice essential to regeneration of the liver.

The researchers also found similar cells in humans.

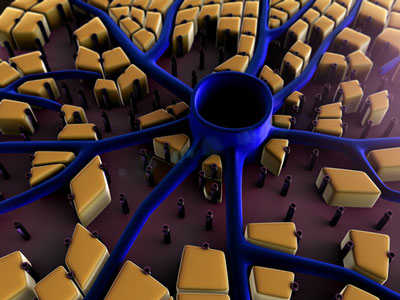

When healthy liver cells are depleted by long-term exposure to toxic chemicals, the newly discovered cells, known as hybrid hepatocytes, generate new tissue more efficiently than normal liver cells. Importantly, they divide and grow without causing cancer, which tends to be a risk with rapid cell division.

“This is the first time anyone has shown how liver cells safely regenerate,” said William Suk, Ph.D., director of the Superfund Research Programme at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), part of NIH.

Liver cancer never originated from hybrid hepatocytes

The researchers studied liver function in mice following long-term exposure to carbon tetrachloride, a chemical commonly associated with Superfund sites. The scientists were able to isolate the hybrid hepatocytes after observing how the tissue regenerated. They then exposed healthy mice to three known cancer-causing pathways and watched the hybrid hepatocytes closely. Liver cancer never originated from these cells.

The research team, led by Michael Karin, Ph.D., distinguished professor of pharmacology and pathology at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine and a member of the prestigious National Academy of Medicine, conducted the research at the UCSD Superfund Research Centre.

“The entire programme at UCSD is focused on the effects of toxicants on liver metabolism and functionality,” said Suk.

One of the goals of the Superfund Research Programme is to better understand how toxic chemicals affect human health. The liver plays an essential role in this process by helping to remove toxicants from the body.

“Hybrid hepatocytes represent not only the most effective way to repair a diseased liver, but also the safest way to prevent fatal liver failure by cell transplantation,” noted Karin.

The findings appear in the journal Cell.

Related topics

Hepatocytes

Related organisations

Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health (NIH)