Lyme disease: mystery, misery and hope

Posted: 15 July 2016 | Victoria White, Digital Content Producer | 2 comments

Drug Target Review recently caught up with Veronica Hughes, CEO of the Caudwell Lyme Disease charity, to find out more about the disease…

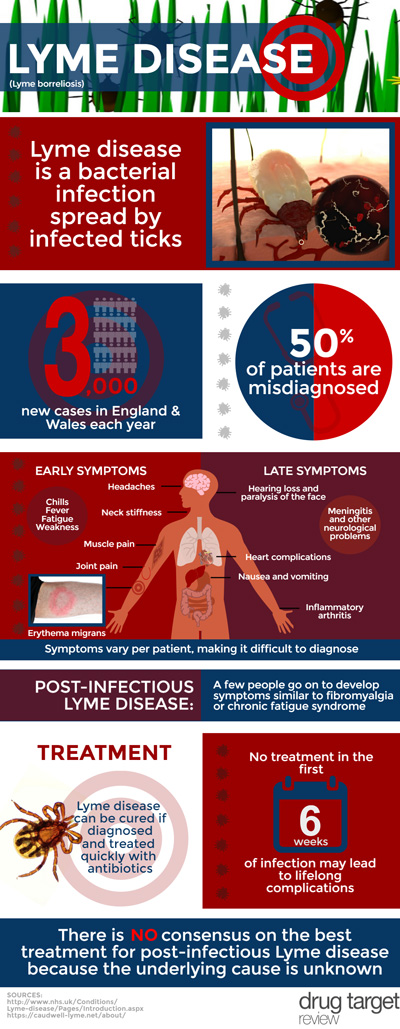

For many of people, summer has arrived and that means many will be partaking in outdoor activities. Those venturing into the countryside and walking in long grass may want to be ‘tick aware’. Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne infection in Europe and North America, with 360,000 cases reported over the last 20 years in Europe alone. It is transmitted by the bite of an infected tick and most commonly appears as a rash around the bite area (erythema migrans).

Despite the number of reported cases per annum, Lyme has been referred to as an “extremely misunderstood” disease which leaves sufferers dealing with a wide-range of debilitating symptoms. Diagnosis is based upon a combination of symptoms and history of tick exposure. Many of the symptoms of Lyme disease are common to other illnesses such as flu. As a consequence, the disease is often left undiagnosed or misdiagnosed.

To compound matters, blood tests are often negative in the early stages of the disease. While most people who contract Lyme disease recover quickly after antibiotic treatment, up to a fifth of patients report persistent symptoms years after they have been told standard tests are negative for the disease. As such, interest in new diagnostic tests is high.

To find out more about Lyme disease, Drug Target Review caught up with Veronica Hughes, CEO of the Caudwell Lyme Disease charity. The Charity wants every GP and consultant to recognise the signs and symptoms of chronic Lyme disease. They want to see accurate testing methods and better treatment options in place within the NHS.

So what are the symptoms of Lyme disease and why is it so difficult to diagnose? The most common symptom is the aforementioned erythema migrans. The rash is often described as looking like a bull’s eye or a target although it can greatly vary in shape and size, as Veronica explains: “The rash comes in a number of different forms which makes it even more complex as a means of diagnosis (in some cases it doesn’t look like a bull’s eye at all and on dark-skinned people it looks like a bruise). It comes and goes over months of illness and is only present for short periods at a time in some patients.”

To further confuse matters, many people with Lyme disease never develop a rash. Veronica explains that the actual percentage of patients who present with erythema migrans is one of the great unknowns of the disease. For example, the British Infection Association states 90% of patients develop the rash, while Public Health England says two thirds of patients in the UK may present with a rash. A patient survey conducted by the National Lyme Borreliosis Testing Laboratory in Scotland found only 48% of patients presented with erythema migrans. As Veronica states: “It is important to emphasise that not seeing this rash is not, in any way, a reassurance that Lyme disease is not present.”

According to the NHS, some people with Lyme disease also experience flu-like symptoms in the early stages, such as tiredness (fatigue), muscle pain, joint pain, headaches, a high temperature (fever), chills and neck stiffness.

More serious symptoms may develop several weeks, months or even years later if Lyme disease is left untreated, such as inflammatory arthritis, problems affecting the nervous system, myocarditis, pericarditis, heart block, heart failure and meningitis. A few people with Lyme disease go on to develop long-term symptoms known as post-infectious Lyme disease. It’s not clear exactly why this happens.

Because many of the symptoms are similar to other conditions, diagnosing Lyme disease is often difficult. Veronica explains: “The current Lyme disease guidelines, issued by Public Health England, state that early Lyme disease symptoms are like flu, which does nothing to help GPs distinguish Lyme cases from the hundreds of flu cases they see every year. Meanwhile medical text books focus on the extreme symptoms like Bell’s palsy or acute myocarditis, which affect fewer than 1% of patients.”

“Caudwell Lyme Disease wants to see a much better description of Lyme symptoms become a part of the treatment guidelines and official information supplied to medical practitioners. The weirder symptoms of Lyme disease are the ones that make many a GP dismiss their Lyme patient as a hypochondriac, but these are the very symptoms that could be telling them they have a case of Lyme disease on their hands, if only they were better informed. These include burning soles of the feet, for example, clumsiness and a tendency to drop things or bump into the furniture, mood swings, inability to focus the eyes when tired, or suddenly forgetting words whilst in the middle of pontificating on one’s favourite subject! A detailed list of such symptoms in the treatment guidelines could help doctors identify Lyme patients before it is too late to cure them.”

As mentioned earlier, there is a lot of interest for new diagnostic tests for the disease. Currently in the UK, two types of blood test are used to diagnose Lyme disease. This is because a single blood test can sometimes produce a positive result even when a person doesn’t have the infection. Also, early on in the disease, blood tests may show a negative result. Veronica explained the issue with the current two-test system: “There is currently no antibody test for Lyme disease which has a sensitivity of over about 57% without making unacceptable reductions in specificity[i]; this means over 40% of patients tested with the two-tier (ELISA and Western blot) system in the UK are given a false negative test result. Public Health England tells GPs that their blood test is fully reliable, when they know it is actually only as reliable as other antibody tests. As a result of this, at least 40% of UK Lyme disease sufferers are denied any antibiotic treatment by their doctors. Caudwell Lyme Disease is in discussions with a number of researchers as part of its goal to help find the best available diagnostic test, or help to develop a new one.”

The current treatment for the disease is a course of antibiotic tablets. Most people will require a two- to four-week course, depending on the stage of the condition. This works for many patients but some fail to respond to treatment, as Veronica explains: “The guidelines for antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease in the UK, as in many other countries, specify relatively short courses of antibiotics. Whilst these work for some patients, they fail to cure others and they are wholly inadequate for patients who already have a long-term infection when treatment is initiated. We desperately need more good-quality research into which antibiotics, or combinations of them, can successfully eradicate such infections. Ticks carry 16 different pathogens which can cause illness in humans and a large percentage of ticks in the UK carry more than one disease, yet we have no screening protocol for these so-called “Lyme disease co-infections”, several of which are well known to cause chronic illness with symptoms very similar to Lyme disease.”

According to United States research organisation Lymedisease.org, one third of Lyme borreliosis patients given no treatment or inadequate treatment in the first six weeks of their infection go on to develop lifelong complications including heart disease, thyroid disease and osteoarthritis.

Veronica explained that this can not only be devastating for the patient, but it can also be expensive: “A Caudwell Lyme Disease survey of 500 patients has found that exactly half of them are too ill to work for the rest of their lives. This is a very complex area to try to research and understand, but Caudwell Lyme Disease is talking to a number of researchers and aims to develop a strategy to achieve better understanding of this complex issue.”

[i] (Sources for the assessment of sensitivity of two-tier testing for Lyme borreliosis: Johnson et al., 1996, Trevejo et al., 1999, Nowakowski et al., 2008, Steere et al., 2008, Branda et al., 2010)

Related conditions

Lyme disease

The concern by Lyme borreliosis charities and patient advocate groups is highly understandable, but the inaccuracy of some the comments in your article on LB serology must be refuted.

The comments, attributed to Veronica Hughes were as follows

‘“There is currently no antibody test for Lyme disease which has a sensitivity of over about 57% without making unacceptable reductions in specificity[i]; this means over 40% of patients tested with the two-tier (ELISA and Western blot) system in the UK are given a false negative test result. Public Health England tells GPs that their blood test is fully reliable, when they know it is actually only as reliable as other antibody tests. As a result of this, at least 40% of UK Lyme disease sufferers are denied any antibiotic treatment by their doctors. Caudwell Lyme Disease is in discussions with a number of researchers as part of its goal to help find the best available diagnostic test, or help to develop a new one.”

The last sentence details a laudable ambition, but it is worth bearing in mind that the top medical diagnosticians in the US and Europe have been vigorously addressing this issue for several decades.

In fact thing are not as bad as suggested. I quote one of the EUCAB diagnostic experts.

Serological testing is not recommended for erythema migrans. Therefore, only disseminated early (stage 2) and late disease (stage 3) should be used for argumentation regarding sensitivity of serological tests. Moreover, usually the question is long lasting late disease (with a chronic course), that should have sensitivity data comparable to results for ACA or Lyme arthritis.

According to an actual systematic review and meta-analysis (Leeflang et al. 2016) sensitivity, though highly heterogeneous, revealed summary estimates (for erythema migrans of 50 % (95 % CI 40 % to 61 %);) for neuroborreliosis 77 % (95 % CI 67 % to 85 %); and for acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans 97 % (95 % CI 94 % to 99 %). Median sensitivity for Lyme arthritis was 96 % (IQR 93 % to 100 %). So, sensitivity for manifestations where serological testing is recommended is between 77% and 97%.

Branda et al 2010: RESULTS: With standard 2-tiered IgM and IgG testing, 31% of patients with active erythema migrans (stage 1), 63% of those with acute neuroborreliosis or carditis (stage 2), and 100% of those with arthritis or late neurologic involvement (stage 3) had positive results. Using new IgG criteria, in which only the VlsE band was scored as a second-tier test among patients with early LD (stage 1 or 2) and 5 of 11 IgG bands were required in those with stage 3 LD, 34% of patients with stage 1, 96% of those with stage 2, and 100% of those with stage 3 infection had positive responses. Both new and standard testing achieved 100% specificity.

Taken the mentioned article from Branda – that is cited to substantiate the idea of a bad serology!!!! – sensitivity was tested to be between 96% and 100%!!!!! for manifestations that are recommended to be tested for antibodies. With a specificity of 100%!!!!”

The comment by EUCALB is completely off the mark. Researchers at the Dr. Paul Duray Research Fellowship Endowment are routinely finding the specific DNA of Borrelia in the blood, CSF and even autopsy brain tissue of patients who were seronegative on the two-tier method promoted by EUCALB.

They have found Borrelia in the dead bodies of people who were negative on the C6 Elisa, the first tier of the test used in the UK’s national testing lab. (The C6 is based on the VlsE mentioned in Eucalb’s comment above.

Many of the specimens were positive for Borrelia miyamotoi, which is genetically closer to the relapsing fever Borreliae than the Burgdorferi group – yet the patients had the same symptoms as in Lyme.

There has been a ile of evidence accumulating over the years showing why borrelia can evade immune recognition using multiple mechanisms including sequestration in the brain, antigenic variation, biofilm formation, and most recently, residence inside of parasitic nematode worms.

The Duray foundation has found Borrelia INSIDE parasitic nematode worms in the autopsy brain tissue of victims of Alzheimer’s, CSF of Multiple sclerosis patients, in autopsy brain of Lewy body dementia victims and in the tumour material of Glioblastoma multiforme.

This work has phenomenal impications , not just for those who are aware they have chronic Lyme, but potentially for the tens of millions with dementia, and the sufferers of other brain diseases.

Sadly there are also phenomenal forces who do not want this work to see the light of day – such as the US Dept of Defense (borrelia is a military pathogen abnd they prefer the science be shrouded in secrecy; allies of the US Dept of Defence (virtually ALL the policy-makers in Lyme are biowarfare scientists); the insurance industry (which stands to lose billions if the reality of persistent, antibiotic-resistant chronic Lyme is acknowledged); and of course the Pharmaceutical giants -who have invested billions in drugs to combat beta-amyloid. All the latest findings, including those of Harvard professors Tanzi and Moir, are indicating that beta-amyloid is NOT the cause of Alzheimer’s and may indeed be an antimicrobial peptide.

One wonders how many more lives must be destroyed before bodies like Eucalb in Europe, CDC in the USA etc agree to stop pulling the wool over the eyes of the public and over the medical profession.