Boosting mitochondria may help regenerate damaged neurons

Posted: 8 June 2016 | Victoria White, Digital Content Producer | No comments yet

Researchers have discovered that boosting the transport of mitochondria along neuronal axons enhances the ability of nerve cells to repair themselves…

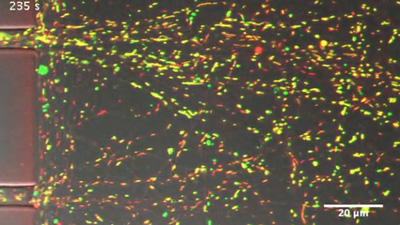

After axonal injury, nearby mitochondria become incapable of producing ATP, as indicated by their change in color from yellow (healthy) to green (damaged). CREDIT: Zhou et al., 2016

Researchers have discovered that boosting the transport of mitochondria along neuronal axons enhances the ability of mouse nerve cells to repair themselves after injury.

Their study suggests potential new strategies to stimulate the regrowth of human neurons damaged by injury or disease.

Neurons need large amounts of energy to extend their axons long distances through the body. This energy – in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) – is provided by mitochondria, the cell’s internal power plants. During development, mitochondria are transported up and down growing axons to generate ATP wherever it is needed. In adults, however, mitochondria become less mobile as mature neurons produce a protein called syntaphilin that anchors the mitochondria in place. Zu-Hang Sheng and colleagues at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke wondered whether this decrease in mitochondrial transport might explain why adult neurons are typically unable to regrow after injury.

Removing syntaphilin facilitated sciatic nerve regeneration

Sheng and his research fellow Bing Zhou initially found that when mature mouse axons are severed, nearby mitochondria are damaged and become unable to provide sufficient ATP to support injured nerve regeneration. However, when the researchers genetically removed syntaphilin from the nerve cells, mitochondrial transport was enhanced, allowing the damaged mitochondria to be replaced by healthy mitochondria capable of producing ATP. Syntaphilin-deficient mature neurons therefore regained the ability to regrow after injury, just like young neurons, and removing syntaphilin from adult mice facilitated the regeneration of their sciatic nerves after injury.

“Our in vivo and in vitro studies suggest that activating an intrinsic growth programme requires the coordinated modulation of mitochondrial transport and recovery of energy deficits. Such combined approaches may represent a valid therapeutic strategy to facilitate regeneration in the central and peripheral nervous systems after injury or disease,” Sheng says.

Related conditions

Stroke