Mini-breast grown in petri-dishes – a new tool for cancer research

Posted: 12 June 2015 | Victoria White

Scientists have created 3D organoid-structures that recapitulate normal breast development and function from single patient-derived cells…

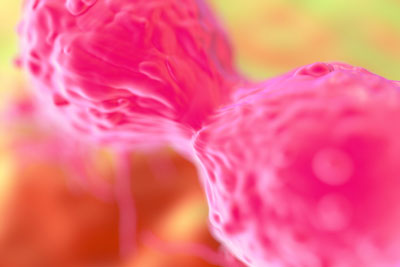

Despite significant progress in the treatment of common types of breast cancer, some aggressive subtypes of the disease are poorly understood and remain incurable.

A new experimental model opens new avenues for mammary gland biology and basic breast cancer research. Together with their colleagues at the LMU Munich, researchers at the Helmholtz Centre in Munich are now able to create three-dimensional organoid-structures that recapitulate normal breast development and function from single patient-derived cells.

The research group, led by Dr Christina Scheel, developed an assay whereby cultured human breast epithelial cells rebuild the three-dimensional tissue architecture of the mammary gland. For this purpose, a transparent gel is used in which cells divide and spread, similar to the developing mammary gland during puberty.

It is crucial to understand the function of breast stem cells to determine how aggressive traits arise in breast cancer cells

Throughout the reproductive lifespan of a woman, the mammary gland is constantly remodelled and renewed in order to guarantee milk production even after multiple pregnancies. Although their exact identity remains elusive, this high cellular turnover requires the presence of cells with regenerative capacity, i.e. stem cells. Breast cancer cells can adopt properties of stem cells to acquire aggressive traits. To determine how aggressive traits arise in breast cancer cells, it is therefore crucial to first elucidate the functioning of normal breast stem cells.

Using their newly developed organoid assay, the researchers observed that the behaviour of cells with regenerative capacity is determined by the physical properties of their environment.

Jelena Linnemann, first author of the study, explains, “We were able to demonstrate that increasing rigidity of the gel led to increased spreading of the cells, or, said differently, invasive growth. Similar behaviour was already observed in breast cancer cells. Our results suggest that invasive growth in response to physical rigidity represents a normal process during mammary gland development that is exploited during tumour progression.”

Co-author Lisa Meixner adds that “with our assay, we can elucidate how such processes are controlled at the molecular level, which provides the basis for developing therapeutic strategies to inhibit them in breast cancer.“

This technological breakthrough provides the basis for many future research projects

Another reason the mini-mammary glands represent a particularly valuable tool is because the cells that build these structure are directly isolated from patient tissue. In this case, healthy tissue from women undergoing aesthetic breast reduction is used. Co-author Haruko Miura explains, “After the operation, this tissue is normally discarded. For us, it is an experimental treasure chest that enables us to tease out individual difference in the behaviour of stem and other cells in the human mammary gland.”

Experimental models that are based on patient-derived tissue constitute a corner stone of basic and applied research. “This technological break-through provides the basis for many research projects, both those aimed to understand how breast cancer cells acquire aggressive traits, as well as to elucidate how adult stem cells function in normal regeneration“, says Scheel.

The research is published in the journal Development.

Related topics

Oncology, Stem Cells

Related conditions

Breast cancer

Related organisations

Cancer Research, Helmholtz Zentrum München