Cell mesh discovery advances understanding of cancer development

Posted: 13 July 2015 | Victoria White

University of Warwick researchers have discovered a cell structure, called ‘the mesh’, which could help scientists understand why some cancers develop…

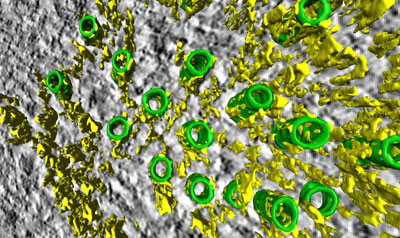

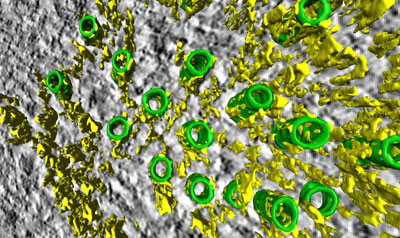

A 3-D view of the mesh: microtubules (green tubes) of the mitotic spindle are held together by a yellow network, the mesh. CREDIT: University of Warwick

University of Warwick researchers have discovered a cell structure which could help scientists understand why some cancers develop.

For the first time a structure called ‘the mesh’, which helps to hold cells together, has been identified, shedding light on the cell’s internal scaffolding.

The findings also have implications for researchers’ understanding of cancer cells as the mesh is partly made of a protein which is found to change in certain cancers, such as those of the breast and bladder.

The research was carried out by a team led by Dr Stephen Royle, associate professor and senior Cancer Research UK Fellow at the division of biomedical cell biology at Warwick Medical School.

Researchers at the University’s Warwick Medical School made the discovery while looking at gaps between microtubules which are part of the cells’ internal structure. One of Dr Royle’s PhD students was examining mitotic spindles in dividing cells using a technique called tomography. This meant that they could see the structure which they later named the mesh. Mitotic spindles are the cell’s way of making sure that when they divide each new cell has a complete genome. Mitotic spindles are made of microtubules and the mesh holds the microtubules together, providing support. While “inter-microtubule bridges” in the mitotic spindle had been seen before, the researchers were the first to view the mesh.

Dr Royle said, “We had been looking in 2D and this gave the impression that ‘bridges’ linked microtubules together. This had been known since the 1970s. All of a sudden, tilting the fibre in 3D showed us that the bridges were not single struts at all but a web-like structure linking all the microtubules together.”

Further study of the mesh might give an insight into why cell division becomes faulty in cancer

The discovery impacts on the research into cancerous cells. A cell needs to share chromosomes accurately when it divides otherwise the two new cells can end up with the wrong number of chromosomes. This is called aneuploidy and this has been linked to a range of tumours in different body organs.

The mitotic spindle is responsible for sharing the chromosomes and the researchers at the University believe that the mesh is needed to give structural support. Too little support from the mesh and the spindle will be too weak to work properly, however too much support will result in it being unable to correct mistakes. It was found that one of the proteins that make up the mesh, TACC3, is over-produced in certain cancers. When this situation was mimicked in the lab, the mesh and microtubules were altered and cells had trouble sharing chromosomes during division.

Dr Emma Smith, senior science communications officer at Cancer Research UK, said, “Problems in cell division are common in cancer – cells frequently end up with the wrong number of chromosomes. This early research provides the first glimpse of a structure that helps share out a cell’s chromosomes correctly when it divides, and it might be a crucial insight into why this process becomes faulty in cancer and whether drugs could be developed to stop it from happening.”

The study findings have been published in the journal eLife.

Related topics

Drug Discovery, Oncology

Related conditions

Breast cancer

Related organisations

Cancer Research, Cancer Research UK, Warwick University