Genetic testing leads to response in MET fusion lung cancer

Posted: 1 September 2017 | Dr Zara Kassam (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have identified a rare fusion involving the gene MET leading researchers to treat the cancer with a targeted therapy…

Researchers have examined the tumour sample from a late-stage lung cancer patient using an assay that detects gene fusions in dozens of genes. The test identified a rare fusion involving the gene MET, leading researchers to treat the cancer with the targeted therapy crizotinib, which inhibits MET signalling.

More than 8 months after the start of the targeted treatment, the patient who was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer continues to show an almost complete response.

“The way we approach the workup and treatment of stage IV lung cancer patients includes broad molecular profiling, so that’s what we did,” said Dr Terry Ng, Senior Fellow in clinical and translational research in thoracic oncology at University of Colorado Cancer Center (CU) and the University of Colorado.

Among the tests used for this molecular profiling was a relatively new assay called Archer FusionPlex, and validated for clinical testing.

Instead of testing for alterations in individual genes – for example, testing separately for changes to known oncogenes ALK, ROS1 or EGFR – the test explored an entire class of genetic changes, testing simultaneously for “gene fusions” in 53 cancer-related genes.

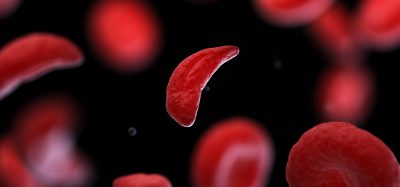

In these gene fusions, pieces of one gene accidentally become attached to pieces from another. This creates “chimeric proteins” – new proteins made from parts of each – that can drive cancer growth. Two well-established examples of this in lung cancer are fusions involving genes ALK and ROS1.

The gene MET has also been identified as a partner in cancer-causing fusions, and, in fact, other changes to the MET gene including mutation of MET, amplification of MET, and something called exon-14 skipping mutations have already been targeted by investigational drugs in lung cancer clinical trials. However, testing for MET fusions has been uncommon.

“The frequency of MET fusions is very low in lung cancer, well below one percent. You would never test for them individually. You need an assay that looks at many things simultaneously to catch these rare events,” says Dr Kurtis Davies, lead assay development scientist Colorado Molecular Correlates Laboratory (CMOCO).

Adding to the challenge is that identifying a MET fusion gene requires not only testing for MET, but testing in a very specific way.

“A lot of tests say they cover MET, but that doesn’t mean they pick up this particular alteration. Depending on how you sequence MET and what regions you sequence, you may or may not find this alteration,” said Dr Robert Doebele, at CU Cancer Center investigator and Associate Professor of Medical Oncology at the CU School of Medicine.

In 2016, the patient who is from out-of-state, planned to spend three months in Denver visiting her daughter. She had previously been diagnosed with lung cancer and knew that while in Colorado she would need care from a local treatment team.

When she came to University of Colorado Hospital, “We could see her tumours growing,” said Dr Ng. The team requested a sample of the patient’s tumour that had been removed during an earlier surgery, and used that sample for molecular testing.

“At CU, in addition to the tests that most community centers would use, looking for things like EGFR, PD-L1, ALK and ROS1, we do a broader panel. We look for KRAS, MET amplification, MET exon 14 skipping mutations, RET gene rearrangements, BRAF-V600 mutations, HER2 mutations and more. All those things were negative. But one other thing that we do is this RNA-based next-generation sequencing assay called FusionPlex. This NGS platform looks for gene fusions in 53 cancer-associated genes. The assay is unique in that is you don’t need to know a gene’s fusion partner to identify that there is a gene fusion,” said Dr Ng.

This is how the team identified the patient’s MET fusion. The next step was deciding how to treat it.

“A lot of people don’t know that the drug crizotinib was originally designed to be an inhibitor of the MET gene product,” Dr Davies said, pointing out that the drug’s first FDA approval was not against MET but against ALK-positive lung cancer and was more recently approved to treat ROS1-positive lung cancer. “But the reality is that most drugs in this class hit many targets. Sometimes that’s detrimental – it hits things you don’t want to hit. This is an example of a case when it’s beneficial.”

In the current patient, this strategy of targeting MET with crizotinib showed dramatic results.

“Her first scan showed an almost complete response, a total absence of lung nodules,” Ng says. Side effects included increased fatigue, “but overall nothing that was life-threatening or would keep her from continuing the drug,” said Dr Ng.

There are many ways a gene can be altered and there are many genes that, when altered, can cause cancer.Testing individually for each possible alteration in every cancer-related gene is not feasible as it would require hundreds of individual tests and many, many thousands of dollars.

The case study by the University of Colorado Cancer Center has been published in the journal JCO Precision Oncology.

Related topics

Gene Testing, Genetic Analysis, Genomics, Oncology

Related conditions

Lung cancer

Related organisations

University of Colorado

Related people

Dr Kurtis Davies, Dr Terry Ng, said Dr Robert Doebele