Lamotrigine found to prevent NF1 brain tumour growth in mice

Posted: 16 April 2024 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

The new findings could result in a clinical trial to assess whether a one-year course of treatment could stop brain tumours.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine have discovered that the epilepsy drug lamotrigine prevents brain tumour formation and growth in two mouse models of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), the genetic condition that causes tumours to grow on nerves throughout the body, including the optic nerves. This finding could lead to a clinical trial to assess whether lamotrigine can delay or stop brain tumours in children with NF1.

Senior author Dr David Gutmann, the Donald O. Schnuck Family Professor of Neurology and the director of Washington University’s Neurofibromatosis Center, explained: “Based on these data, the Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium is considering launching a first-of-its-kind prevention trial…The plan is to enrol kids without symptoms, treat them for a limited time, and then see whether the number of children who develop tumours that require treatment goes down.”

Optic gliomas are the most serious tumours that people with NF1 develop. These affect the optic nerve and generally appear between ages three to seven. Although these tumours are rarely fatal, they cause vision loss in up to a third of patients as well as other symptoms, like early puberty. Standard chemotherapy is only moderately effective at preventing further vision loss and can affect children’s developing brains, resulting in cognitive and behavioral problems.

In a previous study, Dr Gutmann and Dr Corina Anastasaki, assistant professor of neurology and the first author on the new paper, demonstrated that lamotrigine stopped optic glioma growth in NF1 mice by suppressing neuronal hyperactivity. The Neurofibromatosis Clinical Trial Consortium was intrigued by their data but demanded more evidence before they would consider launching a clinical trial. Dr Gutmann and Dr Anastasaki were required to clarify the connection between NF1 mutation, neuronal excitability and optic gliomas; assess whether lamotrigine was effective at the doses already proven safe in children with epilepsy; and conduct these studies in more than one strain of NF1 mice.

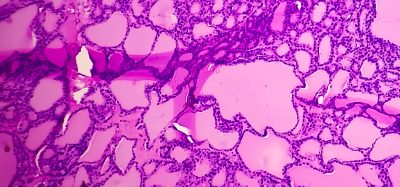

NF1 is a highly variable disease in humans, caused by any one of thousands of different mutations in the NF1 gene. Therefore, repeating experiments in multiple strains of mice enabled the researchers to understand whether lamotrigine was likely to work in people regardless of the underlying mutation.

It was shown that lamotrigine worked in two strains of NF1 mice and worked at lower doses than those used for epilepsy, meaning that it is likely to be safe. Furthermore, they discovered that a short course of the drug had lasting effects, both as a preventive and a treatment. A treatment period of four weeks, starting in mice with 12 weeks of age ceased tumour growth and saw no further damage to the retinas of the rodents’ eyes. Mice that received a four-week course of the drug starting at four weeks of age, before tumours typically emerge, showed no tumour growth even four months after treatment had ended.

These results have led Dr Gutmann to suggest that a one-year course of treatment for young children with NF1, maybe between the ages of two to four, could be enough to reduce their risk of brain tumours. “The idea that we might be able to change the prognosis for these kids by intervening within a short time window is so exciting,” Dr Gutmann commented. “If we could just get them past the age when these tumours typically form, past age seven, they may never need treatment.”

This study was published in Neuro-Oncology.

Related topics

Drug Repurposing, In Vivo

Related conditions

neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)

Related organisations

Washington University School of Medicine