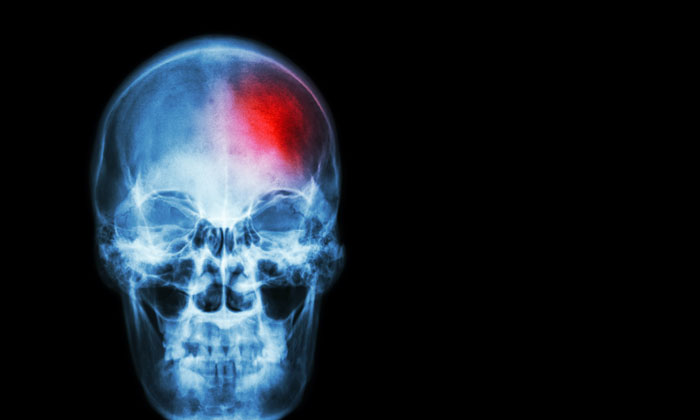

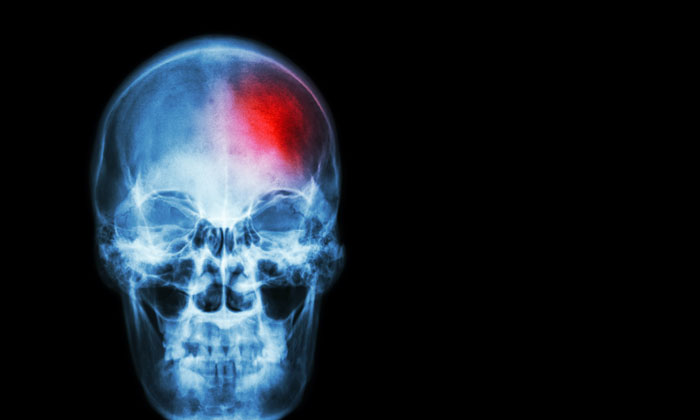

New compound shows promise for stroke recovery

Posted: 24 April 2018 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

Scientists in the U.S. have reported that an experimental compound appears to improve stroke outcome by reducing the destructive inflammation that can often continue months after a person has suffered the stroke.

Rats consuming ‘compound 21’ following a clot-based stroke – the most common type in humans – despite experiencing the same size stroke, have better memory and movement in its aftermath, says Dr. Adviye Ergul, vascular physiologist and Regents’ Professor in the Department of Physiology at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

Commenting on the novel general effects of the compound, senior study author Ergul said: “We don’t see acute neuroprotection, but it definitely affects long-term outcome.”

We think it will help the recovery (of a stroke) and, at this moment, we really have no drugs to do that.”

“Our evidence to date indicates that compound 21 helps directly address lingering inflammation and its destructive impact,” says Dr. Susan Fagan, assistant dean for the University of Georgia College of Pharmacy campus in Augusta, Albert W. Jowdy Professor and Director of the Center for Pharmacy and Experimental Therapeutics at MCG.

In preclinical studies (designed more like clinical trials) relatively young and otherwise healthy rats were given a clot in the middle cerebral artery – a common site for big strokes in humans. They received different doses of compound 21 – known to stimulate the angiotensin type 2 receptor, which is thought to reduce inflammation and improve cell survival – for five days, with the first dose given three, six or 24 hours after stroke. Some rats also received the clot buster tPA, still the only medicine approved by the Food and Drug Administration for stroke, at either two or four hours post stroke and compound 21 at three hours.

Compound 21 effective where FDA-approved drug failed

Neither compound 21 alone or in concert with tPA reduced the size of the stroke, explained Fagan who was also a senior author of the study. In fact, tPA was essentially ineffective in these studies. However, rats that were administered compound 21 had less brain inflammation in the days following a stroke, performed better on cognitive tests and had better nerve and movement function.

The scientists believe that the compound not only inhibits bad responses, such as inflammation and oxidative stress, but also stimulates good ones like brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) – which is known to help ailing brain cells recover – and production of the blood vessel dilator nitric oxide.

Ergul explained that the prevailing thought regarding decline following a stroke has been that increasing cognitive decline with time is due to additional strokes. However, there is evidence that the first stroke alone can initiate a progressive and lasting inflammatory process that can continue to damage the brain for months, or longer.

Noting the current state regarding treatment for this situation, Fagan explains that no prescribed therapies exist to tamp down this inflammation and damage.

“More people are surviving stroke but often with consequences like cognitive deficits and impaired ability to function,” Ergul says.

Even the lowest dose of compound 21 given three hours after stroke resulted in significant improvement in these functions. However, no dose reduced the initial size of the stroke, which is typically determined after about three days. In subsequent studies, the scientists found compound 21 dampened inflammation when given even 24 hours after stroke.

In their follow-up studies, they are giving the compound as far as seven days after – as the stroke moves from the acute to the more chronic stage – ideally to help the immune response be more reparative.

The compound works by stimulating the angiotensin type 2 receptor, a cell receptor known to aid blood vessel dilation, minimise cell death, or apoptosis, and reduce inflammation. The type 2 receptor is expressed less in adults than its antithesis, angiotensin type 1 receptor, which typically mediates the more detrimental effects of the renin-angiotensin system, like high blood pressure and inflammation. In fact, drugs that block the angiotensin type 1 receptor on blood vessels, the heart and other tissues, are among the most prescribed drugs, primarily for high blood pressure and heart failure, she says.

Previous work has indicated that stimulating the angiotensin type 2 receptor could aid stroke recovery and that when the receptor is missing, the size of the brain infarct is larger. Additionally, another drug that increases activity of the receptor, but must be directly injected into the brain, has been shown to improve stroke outcome, according to the researchers.

“We thought that a drug that directly stimulated the angiotensin type 2 receptor – and could be taken by mouth – might work better and decided to look at compound 21,” Fagan says. Even high doses of compound 21 did not affect blood pressure, they noted, which is important given the conflicting evidence regarding whether driving pressure up or down is bad following a stroke.

In keeping with their desire for translatable findings, the scientists are now working to answer such questions as whether the results will hold in female rats, given that only male rats were used in the published study (to eliminate the stroke protection that high oestrogen provides). They also are investigating the compound’s efficacy in the face of existing diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes – two major stroke risks – as well as increasing age.

Many stroke therapies that looked promising in the laboratory have failed in humans, Ergul says, which has led groups like the National Institutes of Health to push for more rigour in study design and reproducibility of results in preclinical trials. This means ensuring that laboratory studies mimic the clinical scenario as closely as possible. In the case of stroke, they suggest studies should include blinding results, so that scientists don’t know which animals have been given which treatment; randomised enrolment of older animals; and looking at the impact of tPA on whichever new therapy is being studied.

Related topics

Disease Research, Drug Leads

Related conditions

Stroke

Related organisations

Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, University of Georgia

Related people

Dr Adviye Ergul, Dr Susan Fagan