SAS1B discovery could fundamentally alter cancer treatment

Posted: 10 September 2015 | Victoria White

The SAS1B protein appears only on egg cells and cancer cells, and could serve as a target for tiny tracking probes created using monoclonal antibodies…

Cancer cells riddled with holes and dying after treatment with an antibody drug conjugate that targets the SAS1B protein on the surface of tumour cells. CREDIT: John Herr | University of Virginia School of Medicine

Researchers from University of Virginia School of Medicine have discovered a new strategy for attacking cancer cells that could fundamentally alter the way doctors treat and prevent the deadly disease.

By more selectively targeting cancer cells, this method offers a strategy to reduce the length of and physical toll associated with current treatments.

“We think we have a way not only to more specifically target cancer cells, but a way that could become a frontline treatment for women who have cancers of many types and want to preserve fertility,” said reproduction researcher John Herr, PhD, of UVA’s Department of Cell Biology.

Herr and his research partner, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology biologist Eusebio Pires, PhD, both specialise in germ cells – the reproductive cells that make up sperm and eggs. While researching new methods of contraception, Pires and Herr discovered a surprising link between developing egg cells and tumours.

At the time, Herr and Pires were studying a protein called SAS1B that is typically only on the surface of developing and mature egg cells. The restriction of SAS1B to growing eggs suggests strategies for developing improved female contraceptives that selectively target only the pool of growing eggs, potentially reducing unwanted side effects of current steroidal contraceptives.

Researchers found SAS1B expressed in a number of cancers

Although the team originally focused on SAS1B because of its possible use in contraception, a single piece of data in the US National Cancer Institute’s GenBank database, showing expression of SAS1B in a uterine cancer, led their team to begin a search for it on the surface of various cancer types. So far, they have found SAS1B expressed in breast, melanoma, uterine, renal, ovarian, head and neck, and pancreatic cancers. There is also evidence to suggest that it appears in bladder cancers.

“The research opens a new field of enquiry, termed cancer-oocyte neoantigens, and reveals a previously little know fundamental aspect of cancer – that many types of cancer, when they dysregulate or go awry, revert back and take on features of the egg, the original cell from which all the tissues in the body derive,” Herr said.

Herr and Pires have found a way to exploit this fundamental insight by developing a method for delivering medication using the SAS1B protein as a target.

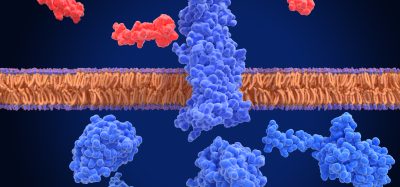

Because the SAS1B protein appears only on egg cells and cancer cells, the molecule can serve as a target for tiny tracking probes created using monoclonal antibodies. Monoclonal antibodies are highly pure antibodies designed to bind to one single target protein with a uniform affinity. The monoclonal antibodies attach to any cell marked with SAS1B proteins. Then the monoclonal antibody-SAS1B complexes can function as tiny injectors for targeted medication.

“You add a SAS1B-targeted antibody with a drug on it, and within 15 minutes of contacting the cancer cells, the antibody binds at the cell surface and the antibody-SAS1B complexes begin the internalization process,” Herr said.

After about an hour, the antibody-SAS1B complexes reach compartments inside the cell and release their toxic drug payload, triggering changes leading to cell death within a few days.

The targeted drug delivery could mean a dramatic reduction in side effects

This kind of targeted drug delivery could mean a dramatic reduction in the difficult side effects of traditional cancer treatment such as hair loss, nausea, anaemia and neuropathy. Both women and men can use the treatment, which is predicted to dramatically limit unwanted side effects on healthy normal cells. For female cancer patients especially, a drug that doesn’t touch their body’s reserve of quiescent eggs could be a huge breakthrough.

While the monoclonal antibodies would have to attack the pool of growing egg cells in addition to the SAS1B positive cancer cells, the ovaries’ supply of dormant eggs would remain healthy and untouched by the treatment. This means normal ovulation could begin again once treatment is complete and oocytes are again recruited to develop and ovulate.

Related topics

Drug Delivery, Drug Discovery, Oncology

Related conditions

Breast cancer, Melanoma

Related organisations

Cancer Research