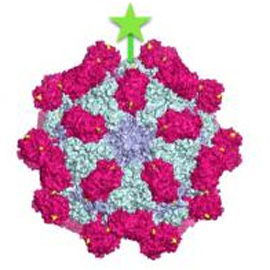

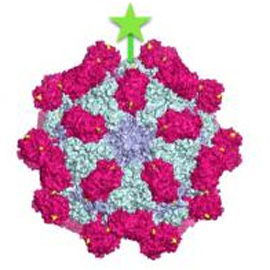

Empty Hepatitis E virus shells used to carry vaccines

Posted: 4 February 2016 | Victoria White | No comments yet

Researchers showed that virus-like particles carrying LXY-30 could home in on breast cancer cells both in a laboratory dish and in a mouse model…

Researchers from UC Davis have developed a way to use the empty shell of a Hepatitis E virus to carry vaccines or drugs into the body.

The technique has been tested in rodents as a way to target breast cancer.

Hepatitis E virus is feco-orally transmitted, so it can survive passing through the digestive system, said Marie Stark, a graduate student working with Professor Holland Cheng in the UC Davis Department of Molecular and Cell Biology.

The researchers prepared virus-like particles based on Hepatitis E proteins. The particles do not contain any virus DNA, so they can’t multiply and spread and cause infections. Such particles could be used as vaccines that are delivered through food or drink. The idea is that you would drink the vaccine, and after passing through the stomach the virus-like particles would get absorbed in the intestine and deliver vaccines to the body.

But the particles could also be used to attack cancer. Stark and Cheng did some tinkering with the proteins, so that they carry sticky cysteine amino acids on the outside. They could then chemically link other molecules to these cysteine groups.

They worked with a molecule called LXY-30 which is known to stick to breast cancer cells. By using a fluorescent marker, they could show that virus-like particles carrying LXY-30 could home in on breast cancer cells both in a laboratory dish and in a mouse model of breast cancer.

Related topics

Drug Delivery

Related organisations

UC Davis