T cells show immunity to a variety of bacteria

Posted: 27 April 2023 | Izzy Wood (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Australian scientists explored a group of bacterial pathogens that share a protein sequence which is recognised by human T cells.

A study from Monash University, Australia, has uncovered a group of divergent bacterial pathogens, including pneumococci, that all share a small highly conserved protein sequence, which is both presented and recognised by human T cells in a conserved population-wide manner.

Typically, T cells of the immune system respond to a specific feature (antigen) of a microbe, thereby generating protective immunity. As reported in Immunity, an the researchers have found an exception to this rule.

The study set out to understand immune mechanisms that protect against pneumococcus, a bacterial pathobiont that can reside harmlessly in the upper respiratory mucosae but can also cause infectious disease, which can range from middle ear and sinus infections to pneumococcal pneumonia and invasive bloodstream infections.

Most currently used pneumococcal polysaccharide-based conjugate vaccines (PCVs) are effective against 10–13 serotypes, but growing serotype replacement becomes a problem. World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 1.6 million people die of pneumococcal disease every year, including 0.7–1 million children aged under 5, most of whom live in developing countries.

The Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute co-led study, in collaboration with the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) and Utrecht University in the Netherlands and Cardiff University in the UK, identified a crucial fragment of the pneumococcal toxin pneumolysin that was commonly presented by a particular class of human antigen presenting molecules, and recognised by T cells from most people who naturally develop specific immunity to pneumococcal proteins.

It was found that the uniformly presented and broadly recognised bacterial protein fragment was not unique for the pneumococcal pneumolysin but was shared by a large family of bacterial so-called cholesterol dependent cytolysins (CDCs). These are produced by divergent bacterial pathogens mostly affecting humans and cause a range of respiratory, gastro-intestinal, or vaginal infectious diseases.

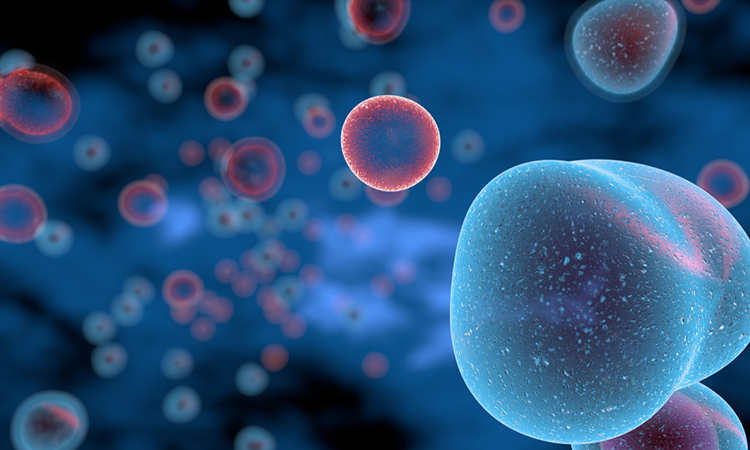

The pneumococci lie in the background, an array of macrophages and dendritic cells are arranged around the central image of a T cell. Rows of TCRs interacting with the identified pneumolysin epitope bound to HLA (white) cross the length and breadth of the artwork, emphasising their centrality in the immune response.

(Credit: Dr Erica Tandori)

First author Dr Lisa Ciacchi said “The use of the National synchrotron was key to provide molecular insight into how the T cell receptors see these conserved antigens when presented by common Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) molecules”.

Co-author Dr Martijn van de Garde explained “We have not yet identified the exact function of the near-ubiquitous T cell populations to this commonly presented conserved protein fragment during ongoing colonisations or infections with CDC producing bacteria. Whether the T cells have a cross-protective mode of action or have an anti-inflammatory tolerising function, remains to be investigated”.

Shared co-author Dr Kristin Ladell said; “The identification of T cells that recognise a ubiquitous bacterial motif using T cell receptors that are shared between individuals with prevalent HLAs is very exciting. Reagents generated for this study can now be used to study patient groups to examine how prevalent these shared TCRs are and how they are related to immune protection”.

Continuing investigations could instruct the development of interventions for people to more efficiently resist or clear CDC-related bacterial diseases.

Related topics

Bacteriophages, Immunology, T cells

Related organisations

Cardiff University, Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute, Monash University, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Utrecht University

Related people

Dr Kristin Ladell, Dr Lisa Ciacchi, Dr Martijn van de Garde