Vaccine strategy devised to boost T-cell therapy

Posted: 12 July 2019 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

A research team has developed a vaccine that advances anti-tumour T-cell populations and allows the cells to invade solid tumours.

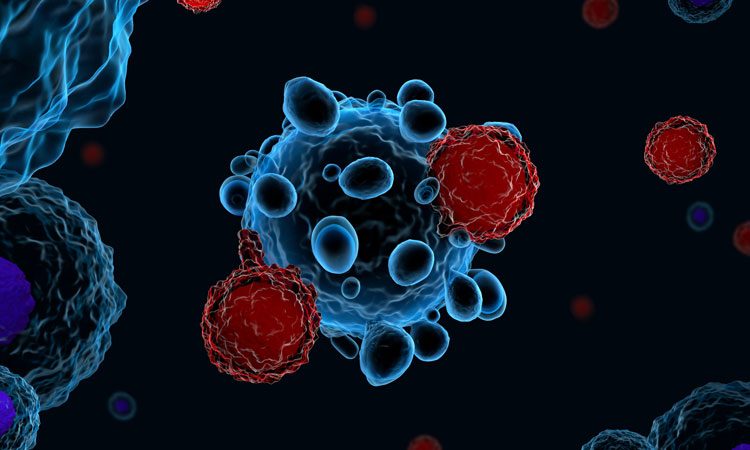

MIT researchers have devised a way to boost CAR T-cell therapy so it can be used against nearly any type of cancer. The team developed a vaccine that advances anti-tumour T-cell population and allows the cells to invade solid tumours.

In a study of mice, the researchers found that they could eliminate solid tumours in 60 percent of the animals that were given T-cell therapy along with the booster vaccination.

“By adding the vaccine, a CAR T-cell treatment which had no impact on survival can be amplified to give a complete response in more than half of the animals,” said Darrell Irvine, senior author of the study.

The team found that they could deliver vaccines more effectively to the lymph nodes by linking them to a lipid tail, which then binds to albumin, allowing the vaccine to be carried directly to the lymph nodes. Additionally, the vaccine contains an antigen that stimulates the CAR-T cells once they reach the lymph nodes.

In tests in mice, the researchers showed that either of these vaccines dramatically enhanced the T-cell response. This boost in the CAR T-cell population eliminated glioblastoma, breast and melanoma tumours in many of the mice.

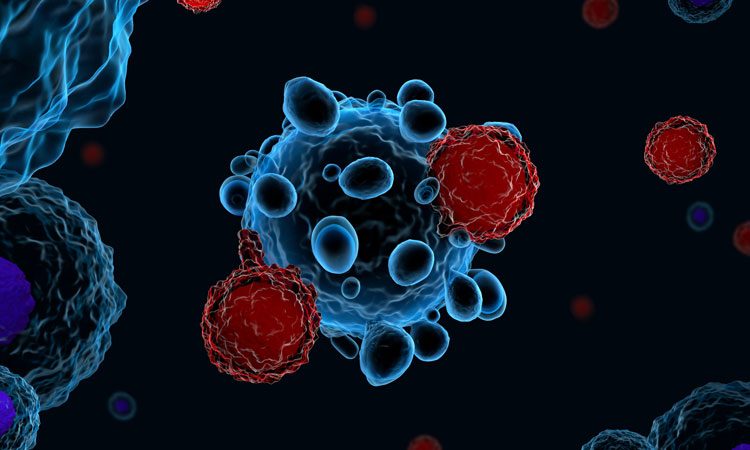

This technique also holds promise for preventing tumour recurrence, Irvine said. About 75 days after the initial treatment, the researchers injected tumour cells identical to those that formed the original tumour and these cells were cleared by the immune system.

About 50 days after that, the researchers injected slightly different tumour cells, which did not express the antigen that the original CAR-T cells targeted; the mice could also eliminate those tumor cells.

This suggests that once the CAR-T cells begin destroying tumours, the immune system is able to detect additional tumour antigens and generate populations of ‘memory’ T cells that also target those proteins.

“There’s really no barrier to doing this in patients pretty soon, because if we take a CAR-T cell and make an arbitrary peptide ligand for it, then we don’t have to change the CAR-T cells,” Irvine said.

The study appears in Science.

Related topics

Research & Development, T cells, Vaccine

Related conditions

Cancer

Related organisations

MIT

Related people

Darrell Irvine