Enzyme substrate mutations promote tumour growth

Posted: 5 July 2023 | Izzy Wood (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Using a newly developed algorithm and a validation study, US researchers find that cancer hijacks a class of enzyme mutations to fuel tumorigenesis.

Cancer spreads throughout the human body in cunning ways. For example, it can manipulate our genetic make-up, take over specific cell-to-cell signalling processes, and mutate key enzymes to promote tumour growth, resist therapies, and hasten its spread from the original site to the bloodstream or other organs.

Enzyme mutations have been of great interest to scientists who study cancer.

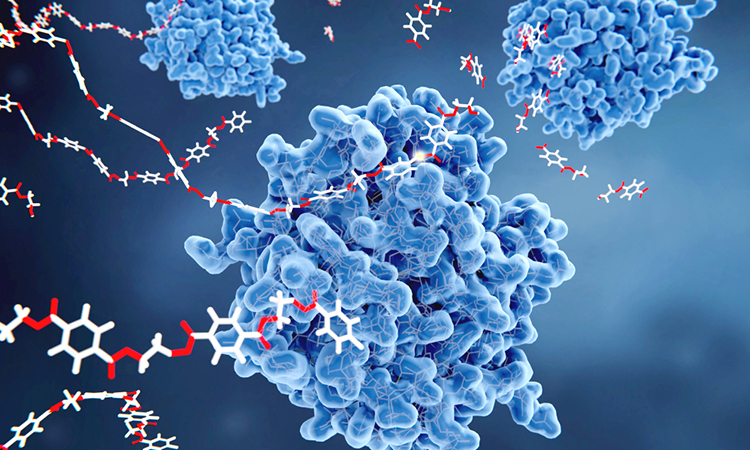

Scientists in labs at University of North Carolina’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Centre have been studying mutations of enzyme recognition motifs in substrates, which may more faithfully reflect enzyme function with the potential to find new targets or directions for cancer treatment. Their results were published in Journal of Experimental Medicine.

“We think understanding the roles of mutations on enzyme substrates, instead of the enzyme as a whole, may help to improve efficacy of targeted therapies, especially for enzymes that have both oncogenic and tumour suppressive function through controlling distinct subsets of substrates,” said Dr Jianfeng Chen, who is first author and a postdoctoral fellow in the UNC Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

Using the developed algorithm and information from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), they found that the highest rate of mutation occurs in the AGC kinase motif called RxRxxS/T. RxRxxS/T is a short, recurring pattern that is shared among the AGC family of ~60 kinases. These enzymes play critical roles in metastasis, proliferation, drug resistance, and development.

“We found that cancer tried to either evade or create mutations on these RxRxxS/T motifs to give itself more advantages for tumor growth and survival,” explained Dr Pengda Liu, who is an Associate Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

The team conducted a validation study on the AGC kinase motif mutations associated with colorectal cancer, the second most lethal cancer and the third most prevalent malignant tumour worldwide. Currently, colorectal cancer has a 5-year survival rate of 12 percent.

They discovered that colon cancer hijacks BUD13 mutations, a protein-coding gene, to sidestep the phosphorylation that are carried out by AGC kinase. Colon cancer ultimately prefers these BUD13 mutations because it gains an additional benefit by inactivating an E3 ligase called Fbw7. Turning off Fbw7, a crucial tumour suppressor, causes an increase in tumour growth and therapy resistance.

In addition to their findings on Fbw7 inactivation, the research team also found that the BUD13 tumour cells were more susceptible to the inhibition of mTORC2 kinase, revealing a new, potential targeted therapy for colon cancer patients bearing that have the BUD13 mutation.

Related conditions

Colon cancer, tumour development

Related organisations

University of North Carolina’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Centre

Related people

Dr Jianfeng Chen, Dr Pengda Liu