The hope of rejuvenation: using plasma to reverse ageing in mice

Posted: 8 July 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have found that a plasma exchange process can act as a molecular reset button for old blood, improving the health of ageing mice.

In 2005, University of California (UC) Berkeley researchers made the discovery that making conjoined twins out of young and old mice – so that they share blood and organs – can rejuvenate tissues and reverse the signs of ageing in old mice. The finding sparked studies into whether young blood contains special proteins or molecules that could serve as a ‘fountain of youth’ for mice and humans alike.

However new research by the same team shows that similar age-reversing effects can be achieved by simply diluting the blood plasma of old mice – no young blood needed.

In the study, published in the journal Aging, the team reveal that replacing half of the blood plasma of old mice with a mixture of saline and albumin – where the albumin replaces protein lost when the original blood plasma was removed – has the same or stronger rejuvenation effects on the brain, liver and muscle than pairing with young mice or young blood exchange. According to the researchers, performing the same procedure on young mice had no detrimental effects on their health.

The scientists say this discovery shifts the dominant model of rejuvenation away from young blood and toward the benefits of removing age-elevated and potentially harmful factors in old blood.

Drawing conclusions

In humans, the composition of blood plasma can be altered in a clinical procedure called therapeutic plasma exchange, or plasmapheresis, which is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating a variety of autoimmune diseases.

However, this evidence may not be enough for some patients to give up hope: “I think it will take some time for people to really give up the idea that that young plasma contains rejuvenation molecules, or silver bullets, for ageing,” said Dobri Kiprov, a medical director of Apheresis Care Group and a co-author of the paper. “I hope our results open the door for further research into using plasma exchange – not just for ageing, but also for immunomodulation.”

Building on past research

In the early 2000s, the researchers suspected that the body’s ability to regenerate damaged tissue remains with us into old age in the form of stem cells, but that somehow these cells get turned off through changes in our biochemistry as we age.

…the plasma exchange process acts almost like a molecular reset button”

“We had the idea that ageing might be really more dynamic than people think,” Conboy said. “We thought that it could be caused by transient and very reversible declines in regeneration, such that, even if somebody is very old, the capacity to build new tissues in organs could be restored to young levels by basically replacing the broken cells and tissues with healthy ones and that this capacity is regulated through specific chemicals which change with age in ways that become counterproductive.”

After the team published their 2005 work, many researchers seized on the idea that specific proteins in young blood could be the key to unlocking the body’s latent regeneration abilities. However, in the original report and in a more recent study, when blood was exchanged between young and old animals without physically joining them, young animals showed signs of ageing. These results indicated that that young blood circulating through young veins could not compete with old blood.

As a result, the researchers pursued the idea that a build-up of certain proteins with age is the main inhibitor of tissue maintenance and repair and that diluting these proteins with blood exchange could also be the mechanism behind the original results. Therefore, the researchers realised that instead of adding proteins from young blood, which could do harm to a patient, the dilution of age-elevated proteins could be therapeutic, while also allowing for the increase of young proteins by removing factors that could suppress them.

A molecular ‘reset’ button

To test this hypothesis, the team came up with the idea of performing ‘neutral’ blood exchange. Instead of exchanging the blood of a mouse with that of a younger or an ageing animal, they would simply dilute the blood plasma by swapping out part of the animal’s blood plasma with a solution containing plasma’s most basic ingredients: saline and a protein called albumin. The albumin included in the solution simply replenished this abundant protein, which is needed for overall biophysical and biochemical blood health and was lost when half the plasma was removed.

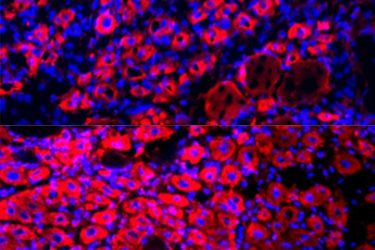

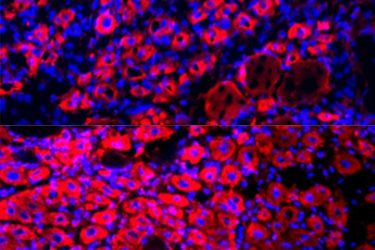

A new study by University of California Berkeley, found that older mice grew significantly more new muscle fibres, shown as pink “doughnut” shapes, after undergoing a procedure that effectively diluted the proteins in their blood plasma (bottom) than they did before they underwent the procedure (top). The research team is currently finalising clinical trials to determine if a modified plasma exchange in humans could be used to treat age-associated diseases and improve the overall health of older people [credit: Irina Conboy].

“We thought, ‘What if we had some neutral age blood, some blood that was not young or not old?'” said Michael Conboy, senior researcher and lecturer in the Department of Bioengineering at UC Berkeley and co-author of the new study. “We’ll do the exchange with that and see if it still improves the old animal. That would mean that by diluting the bad stuff in the old blood, it made the animal better. And if the young animal got worse, then that would mean that that diluting the good stuff in the young animal made the young animal worse.”

After finding that the neutral blood exchange significantly improved the health of old mice, the team conducted a proteomic analysis of the blood plasma of the animals to find out how the proteins in their blood changed following the procedure. They performed a similar analysis on blood plasma from humans who had undergone therapeutic plasma exchange.

They found that the plasma exchange process acts almost like a molecular reset button, lowering the concentrations of a number of pro-inflammatory proteins that become elevated with age, while allowing more beneficial proteins, like those that promote vascularisation, to rebound in large numbers.

“A few of these proteins are of particular interest and in the future, we may look at them as additional therapeutic and drug candidates,” Conboy said. “But I would warn against silver bullets. It is very unlikely that ageing could be reversed by changes in any one protein. In our experiment, we found that we can do one procedure that is relatively simple and FDA-approved, yet it simultaneously changed levels of numerous proteins in the right direction.”

The research team say they are now going to conduct clinical trials to better understand how therapeutic blood exchange might best be applied to treating human ailments of ageing.

Related topics

Drug Targets, Protein, Proteomics, Regenerative Medicine, Research & Development

Related organisations

University of California (UC) Berkeley

Related people

Dobri Kiprov, Michael Conboy, Professor Irina Conboy