Researchers discover compound that could treat Chagas disease

Posted: 14 September 2022 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Using screening techniques, researchers have identified the compound called AN15368 which works as an antiparasitic against Chagas disease.

Researchers from the University of Georgia, US have discovered a potential treatment for Chagas disease, marking the first medication with promise to successfully and safely target the parasitic infection in more than 50 years. Human clinical trials of the drug, an antiparasitic compound known as AN15368, will hopefully begin in the next few years.

“I am very optimistic,” said Professor Rick Tarleton, corresponding author of the study. “I think it has a really strong chance of being a real solution, not just a stand-in for something that works better than the drugs we currently have.”

Chagas disease is most common in Latin American countries, particularly in low-income areas where housing is not ideal. Some of the countries with the highest rates of the disease include Bolivia, Venezuela, Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Brazil.

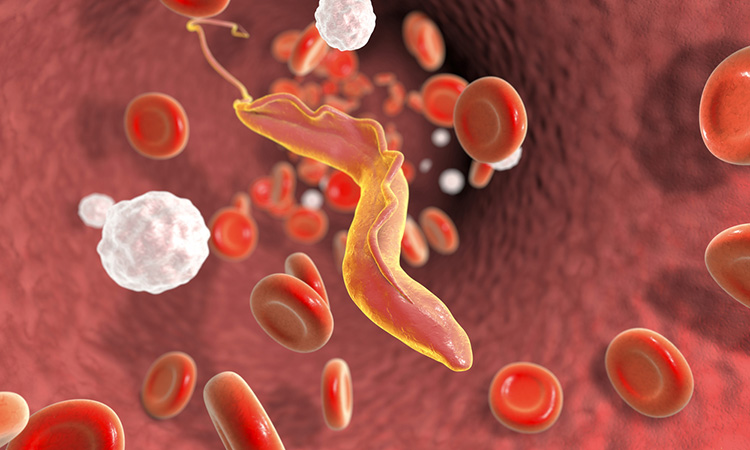

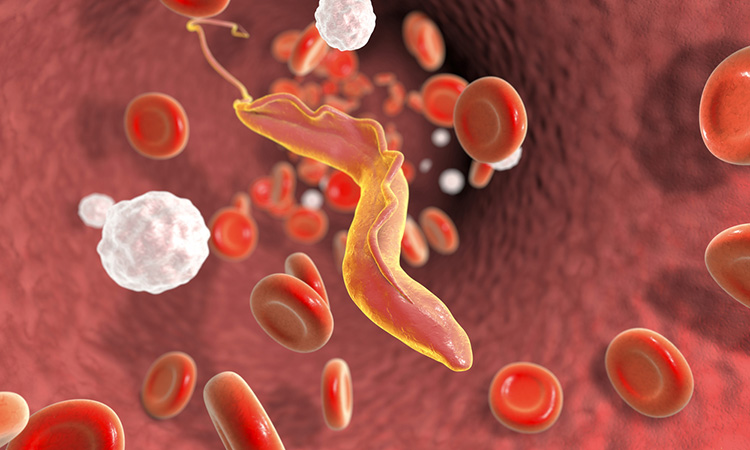

The new drug works by targeting the parasite that causes the disease, Trypanosoma cruzi, also known as T. cruzi. Published in Nature Microbiology, the study found the new medication was 100 percent effective in curing mice and non-human primates that were naturally infected by the parasite at a research facility. The animals also experienced no significant side effects from exposure to the drug.

The researchers used rapid drug screening to discover a series of benzoxaborole compounds with nanomolar activity against extra- and intracellular stages of T. cruzi. Identifying the prodrug AN15368, the team revealed that this targets the messenger RNA processing pathway in T. cruzi. AN15368 was found to be active in vitro and in vivo against a range of genetically distinct T. cruzi lineages.

“We have got something that is as close to effective as it can be in what is as close to a human as it could be and there are not any side effects. That really de-risks it by a lot going into humans,” Tarleton said. “It does not make it fail-safe, but it moves it much further along.”

Related topics

Drug Development, Drug Discovery, Drug Leads, Hit-to-Lead, Screening, Small Molecules

Related conditions

Chagas disease

Related organisations

University of Georgia

Related people

Professor Rick Tarleton