Targeting the clock: new drug disrupts glioblastoma stem cells

Posted: 19 May 2025 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

Scientists have developed a new drug, SHP1705, that targets hijacked circadian clock proteins used by glioblastoma stem cells to grow and resist treatment.

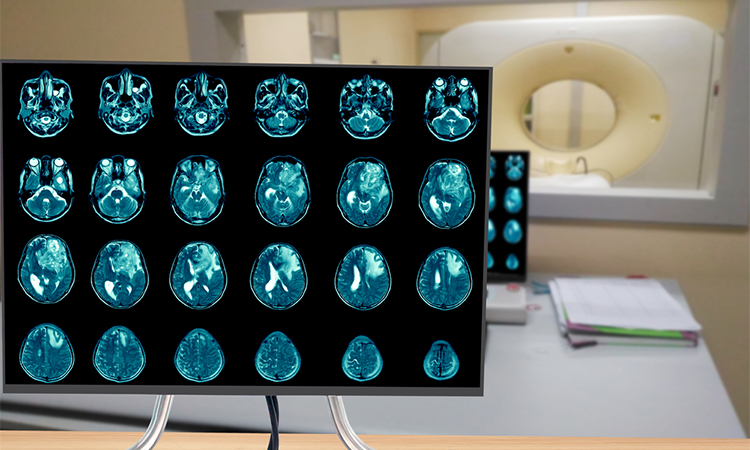

Glioblastoma, the most aggressive form of brain cancer in adults, is notoriously difficult to treat. While most patients undergo surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, tumours often return, driven by a stubborn population of glioblastoma stem cells.

In a series of preclinical studies published in Neuro-Oncology, an international research team led by Dr Steve A. Kay of the Keck School of Medicine of USC and Dr Jeremy Rich of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced that a new compound, SHP1705, disrupts the circadian clock machinery glioblastoma cells rely on to survive and multiply.

Clock proteins: a new vulnerability in cancer

Circadian clock proteins help regulate the body’s internal rhythms, including sleep-wake cycles and cellular functions. But in glioblastoma, cancer stem cells hijack these proteins, particularly CRY2, to drive tumour growth and resist treatment. SHP1705, a CRY activator, is designed to restore activity to this suppressed protein, essentially turning the cancer’s own tools against it.

Automation now plays a central role in discovery. From self-driving laboratories to real-time bioprocessing

This report explores how data-driven systems improve reproducibility, speed decisions and make scale achievable across research and development.

Inside the report:

- Advance discovery through miniaturised, high-throughput and animal-free systems

- Integrate AI, robotics and analytics to speed decision-making

- Streamline cell therapy and bioprocess QC for scale and compliance

- And more!

This report unlocks perspectives that show how automation is changing the scale and quality of discovery. The result is faster insight, stronger data and better science – access your free copy today

“We have mounting evidence that clock proteins can be co-opted by brain cancer stem cells to fuel their growth,” said Dr Kay. “If we can successfully target the circadian clock, these cells lose their ability to replicate.”

Unlike earlier clock-targeting drugs, SHP1705 selectively boosts CRY2 activity in glioblastoma cells without disrupting healthy brain cells, where CRY2 is already active. This precision targeting is key to the drug’s effectiveness, and its safety profile.

Promising preclinical results

In lab tests, SHP1705 impaired the survival of glioblastoma stem cells while sparing normal cells. It worked on both chemotherapy-sensitive and chemotherapy-resistant glioblastoma cell lines, showing potential as a treatment, even when tumours have relapsed after standard care.

Animal studies supported these findings, with mice treated with SHP1705 exhibiting slower tumour growth and longer survival. The compound also appeared to increase the cancer’s sensitivity to radiation therapy, making existing treatments more effective.

Researchers also tested SHP1705 in combination with another circadian-targeting drug, SR29065, developed at the Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute. Together, the two compounds produced even better results, suggesting a powerful synergy that could be explored in future therapies.

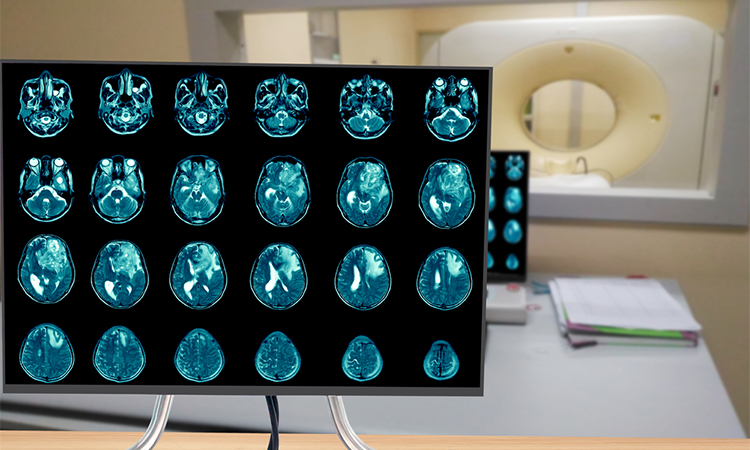

From lab to clinic

A phase I clinical trial conducted by Synchronicity Pharma, a biotech company co-founded by Dr Kay, confirmed SHP1705’s safety in humans. Fifty-four healthy participants tolerated the oral medication well, reporting only minor side effects such as headache and nausea.

The team is now preparing for a phase II clinical trial, which will test SHP1705 in patients with glioblastoma, alongside current standard treatments.

“Right now, the standard of care does not address glioblastoma stem cells that drive the cancer’s recurrence,” said Dr Priscilla Chan, the study’s first author and a postdoctoral researcher at USC. “Our hope is that SHP1705 can help close that gap.”

Beyond glioblastoma

Hijacked clock proteins may play broader roles in cancer biology, such as weakening the immune response and promoting blood vessel growth to support tumours. As researchers continue to explore these mechanisms, compounds like SHP1705 may provide new therapeutic opportunities, not just for glioblastoma, but for other hard-to-treat cancers as well.

Related topics

Cancer research, Clinical Trials, Drug Discovery, Drug Discovery Processes, Drug Targets, Molecular Biology, Oncology, Therapeutics, Translational Science

Related conditions

Cancer, Glioblastoma

Related organisations

Keck School of Medicine of USC, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill