New cancer immunotherapy shows promise in early tests

Posted: 3 July 2018 | Dr Zara Kassam (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers report that in preclinical models they can amplify macrophage immune responses against cancer using a self-assembling supramolecule…

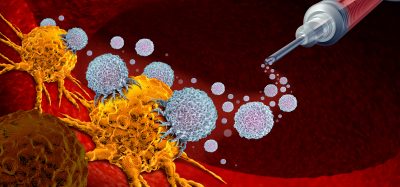

Much cancer immunotherapy research has focused on harnessing the immune system’s T cells to fight tumours, “but we knew that other types of immune cells could be important in fighting cancer too,” says Ashish Kulkarni at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Now he and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, with others, report that in preclinical models they can amplify macrophage immune responses against cancer using a self-assembling supramolecule.

As immune cells, macrophages usually eat foreign invaders including pathogens, bacteria and even cancer cells, Dr Kulkarni explains, but one of the two types do not always do so. Macrophage type M1s are anti-tumorigenic, but M2s can be recruited by tumour cells to help them grow. Also, tumour cells overexpress a protein that tells the macrophages, “don’t eat me.” In this way, pro-tumorigenic macrophages may make up 30 to 50 percent of a tumour’s mass, says the biomedical engineer and lead author of the new study.

Dr Kulkarni adds, “With our technique, we’re re-programming the M2s into M1s by inhibiting the M2 signalling pathway. We realised that if we can re-educate the macrophages and inhibit the ‘don’t eat me’ protein, we could tip the balance between the M1s and M2s, increasing the ratio of M1s inside the tumour and inhibiting tumour growth.” Details appear in the current online issue of Nature Biomedical Engineering.

To address both the M2 “re-education” problem and to enhance the macrophages’ capacity to eat tumour cells, the researchers used what they call a bi-functional or “one-two punch,” says Dr Kulkarni. He and research technician Anujan Ramesh, with colleagues in India and at Harvard Medical School’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, used a multi-component supramolecular system that self-organises at the nanoscale to deliver an antibody inhibitor plus a drug inside the tumour. “This is the first time anyone has combined these two, a drug that targets M2 macrophages and an antibody that inhibits ‘don’t eat me the signal,’ in one delivery system,” Dr Kulkarni notes.

He adds, “We feel this new approach provides a complementary one that can be used along with other therapies. We tested it in melanoma and breast cancer preclinical models, two aggressive cancers, and we plan to try it on different types of cancer and in combination with other current therapies like T-cell-based therapies now used in clinics.”

The researchers tested the supramolecular therapeutic in animal models of the two forms of cancer, comparing it directly with a drug currently available in the clinic. Mice that were untreated formed large tumours by Day 10, they report. Mice treated with currently available therapies showed decreased tumour growth. But mice treated with the new supramolecular therapy had complete inhibition of tumour growth. The team also reported an increase in survival and a significant reduction in metastatic nodes.

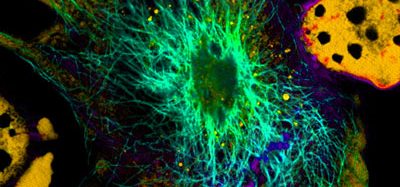

Co-author Shiladitya Sengupta at Brigham and Women’s Hospital says, “We can actually see macrophages eating cancer cells,” citing confocal microscopy images in the paper that show macrophages engulfing cancer cells.

Dr Kulkarni says next steps are to continue testing the new therapy in preclinical models to evaluate safety, efficacy and dosage. The supramolecular therapy they have designed has been licensed and they hope to move the therapeutic into clinical trials if preclinical testing continues to show promise.

Related topics

Disease Research, Immunotherapy, Oncology, T cells, Target Molecule, Target Validation

Related conditions

Cancer

Related organisations

Brigham and Women's Hospital, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Related people

Anujan Ramesh, Ashish Kulkarni, Shiladitya Sengupta