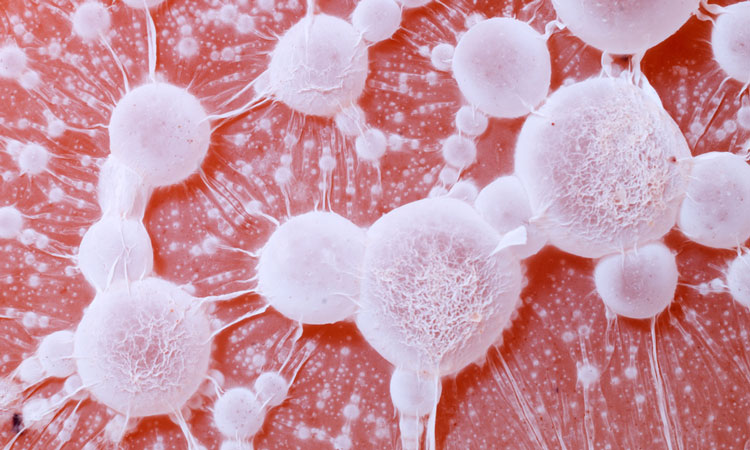

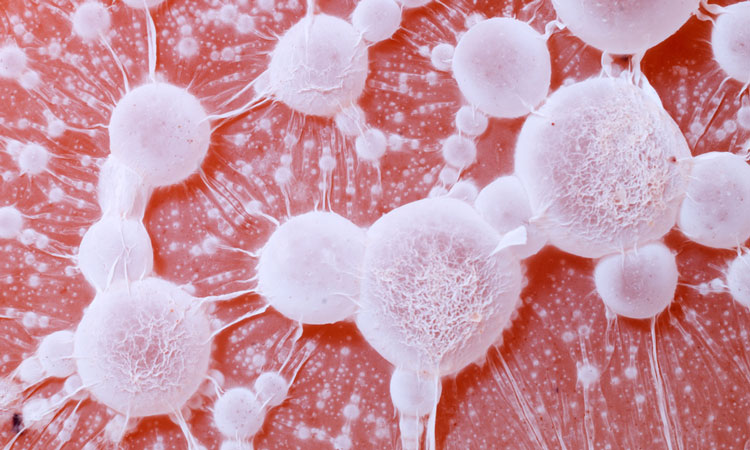

Investigating tumour microenvironments for more effective treatments

Posted: 17 October 2018 | Iqra Farooq (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Tumour microenvironments give insights into more effective therapies against lung cancer, a bigger killer than colon, prostrate and breast cancers combined…

Researchers have gained insights into the microenvironment of different types of lung tumours, describing how the cell ecosystems may affect response to treatment.

The microenvironment of a cell impact how it grows, behaves and communicates with other nearby cells. Researchers aim to understand the microenvironment of the disease cells, such as cancer cells, to identify opportunities for therapeutic intervention, and possible treatment regimes.

According to the American Cancer Society, lung cancer kills more people each year than colon, prostrate and breast cancers combined. Thus, it is imperative that precursors and behaviours of lung cancer are understood to enable the improvement of treatments.

“We sought to figure out why the immune microenvironment of lung cancer types were different,” said Dr Trudy Oliver, researcher at the Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) at the University of Utah.

“We know that different kinds of tumor cells interact with different kinds of immune cells, and these immune cells have functions that can help or hurt the tumor. Essentially, tumors get these immune cells to do their dirty work for them,” said Dr Oliver. “We noticed in both mice and in people that some tumors clinically thought of under the same umbrella are distinct in many ways that were not previously understood. Most strikingly, different lung tumor types were recruiting different types of immune cells.”

The team used single-cell sequencing technology and a specifically developed mouse model to identify the role of neutrophils in lung cancer. Previously, it has been shown that poor prognosis in lung cancer and poor response to immunotherapy treatment for lung cancer were associated with high levels of neutrophils.

“The association of high presence of neutrophils with a bad response to immunotherapy means neutrophils might be a target for scientists to develop new treatments to help people who aren’t responding well to currently available drugs,” Dr Oliver suggested. The team found that the tumors changed the behavior of the neutrophils, causing inhibition of their normal roles and influencing them to behave in ways that supported tumor growth.

“It is both challenging and exciting to study how cancer cells shape their environment to become more favorable for the cancer,” said Gurkan Mollaoglu, a PhD student conducting the laboratory work. “The mouse models that we developed here are powerful tools that mirror many features of human tumors. Using these models, we showed how cancer cells modify their microenvironment and how the altered microenvironment, in return, favors cancer cells.”

In future, the team plan to characterise what the neutrophils do to help tumours, and if by attacking these molecules, lung cancer therapies would become more effective.

The results of the study were published in the journal Immunity.

Related topics

Disease Research, Drug Discovery Processes, In Vivo, Microbiology, Research & Development, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Lung cancer

Related organisations

Huntsman Cancer Institute

Related people

Dr Trudy Oliver, Gurkan Mollaoglu