Mutated PCSK9 gene protects against liver damage and cardiovascular disease, say researchers

Posted: 20 November 2020 | Hannah Balfour (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Scientists suggest the PCSK9Q152H gene variant may act as a “fountain of youth”, allowing people to live longer, healthier lives.

A gene mutation found in a few French-Canadian families protects them from various age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease and liver diseases, according to a new report.

In their studies looking at a rare mutation of the proprotein convertase subtilising/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) gene, researchers at McMaster University, the Montreal Clinical Research Institute and the University of Montreal, all Canada, found the loss-of-function PCSK9 Gln152His (PCSK9Q152H) mutation may allow people who harbour it to live longer, healthier lives.

Their study, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, is based on previous research by Montreal Clinical Research Institute endocrinologist, Michel Chrétien, who is also an emeritus professor at the University of Montreal. In 2011, Chrétien published a study which showed that expression of the PCSK9Q152H mutation in the liver lowers a person’s plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol (the type that can build up in blood vessels) and thereby prevents the development of cardiovascular disease.

According to that 2011 study, people harbouring the mutation were surprisingly healthy well into their late 80s and mid-90s. Aside from their low risk of cardiovascular diseases, these people also had completely normal liver function (not typical of that age range). However, exactly how the PCSK9Q152H mutation results in these effects has remained a mystery, until now.

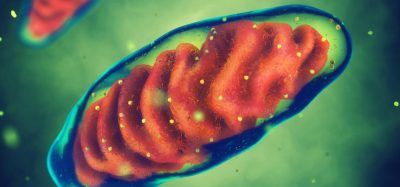

In the new study, the McMaster researchers demonstrated that overexpression of this gene variant in the livers of mice protects them from dysfunction and injury of their liver. It also greatly reduced their circulating PCSK9 levels, in people this is associated with lowered LDL-cholesterol and a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

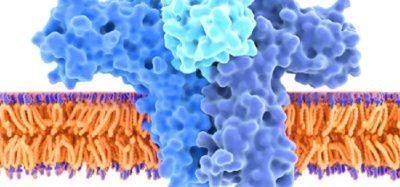

“When we initiated these studies, we had speculated that introducing the mutant PCSK9Q152H protein into the liver of mice would cause liver injury or dysfunction,” said vascular biologist Richard Austin, a medical professor at McMaster University and one of the senior authors of the study. But “to our amazement, overexpression of the mutant gene variant in the livers of mice failed to cause stress in the cellular manufacturing and packaging system called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and actually protected against ER stress-induced liver injury,” added Paul Lebeau, who co-lead the study with Austin and is also a vascular biologist at McMaster University.

In their laboratory, the team went on to show that overexpression of the PCSK9Q152H gene variant greatly increases the stability of key ER stress response chaperones in liver hepatocytes, namely GRP78 and GRP94, thereby preventing liver damage driven by ER stress.

“These are exciting findings – what we have found may represent a kind of fountain of youth,” said Austin. “Now we want to see whether we can come up with a gene therapy approach to overexpress this specific mutant gene variant in the liver and thereby offer an innovative treatment for a number of diseases that normally lead to early death.”

Chrétien added: “These results from Dr Austin’s group are particularly gratifying since they experimentally explain that this gene mutation, known to lower cardiovascular accidents, also protects against liver injury and dysfunction, even in individuals who are in their late 80s and mid-90s. Furthermore, these findings should allow us to determine whether this unique mutation provides additional protection against liver diseases such as cancer, over and above its protective effect against cardiovascular accidents.”

Related topics

Analysis, Disease Research, Genomics, In Vivo, Targets, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Cardiovascular disease, Liver disease

Related organisations

McMaster University, Montreal Clinical Research Institute, University of Montreal

Related people

Michel Chrétien, Paul Lebeau, Richard Austin