Possible method to apply CAR T-cell therapy to solid tumours developed

Posted: 19 March 2021 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

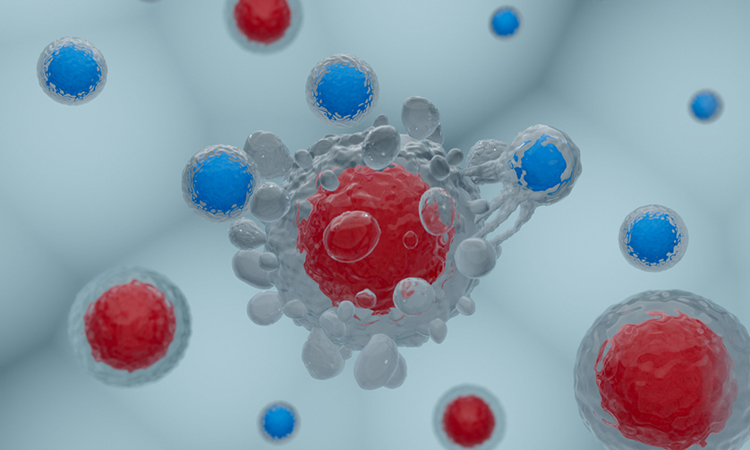

Researchers have developed a CAR T-cell engineering technique to ensure that only cancer cells are targeted, leaving healthy cells alone in solid tumours.

According to scientists, the application of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells to solid tumours has been difficult – targeting the therapy at just the tumour is challenging when the cancer type is not associated with any specific surface structure. Now, a new study has identified a potential solution to applying CAR T-cell therapy to solid tumours by programming CAR T cells so that they only kill cancer cells, leaving healthy cells that have the same marker protein as cancer cells alone.

The researchers, from the University of Helsinki, Finland, say that in many cancer types, there is an abundance of a specific protein on the tumour’s surface, but as the protein also occurs in low numbers in normal tissue, CAR T-cell therapy is not able to discriminate between target protein levels, which can result in fatal adverse effects associated with the treatment.

The team explain that HER2 is a protein characteristic of, among others, breast cancer, ovarian cancer and abdominal cancers. The protein can also occur in great numbers on the surface of tumour cells, since, as a result of gene amplification, HER2 expression can be multiplied in tumours.

The new CAR T-cell engineering technique developed by the researchers is based on a two-step identification process of HER2 positive cells. Thanks to the engineering, the researchers were able to produce a response where CAR T cells kill only the cancer cells in the cancer tissue.

“Our solution requires the preliminary identification of the surface structures associated with the cancer. When the preliminary recognition ability that induces the CAR construct is adjusted to require a binding affinity that is different from the affinity used by CAR to direct the killing of these cells, an extremely accurate ability to differentiate between cells based on the amount of target protein on their surface can be programmed in this two-step ‘circuit’ which controls the function of killer T cells,” said Professor Kalle Saksela, one of the lead researchers.

“We are very excited about these results and we are currently developing the technique so that it could be used to treat ovarian cancer. As the work progresses, the aim is to apply the technique itself and the targeting molecules of CAR constructs even more broadly to malignant solid tumours. Our goal is to develop ‘multi-warhead missiles’, against which cancer cells will find it difficult to develop resistance,” said postdoctoral researcher Anna Mäkelä.

The study was published in Science.

Related topics

Immuno-oncology, Immunotherapy, Oncology, Precision Medicine, T cells

Related conditions

abdominal cancer, Breast cancer, Cancer, Ovarian cancer

Related organisations

University of Helsinki

Related people

Anna Mäkelä, Professor Kalle Saksela