Bacteria in a tumour’s microbiome could influence how cancer responds to treatment

Posted: 23 November 2022 | Izzy Wood (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

US researchers find that bacteria could help tumours progress and resist treatment.

Researchers at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Centre, US, revealed how bacteria infiltrate tumours and could be helping tumours progress and spread.

The research team also showed that the different microbial players in a tumour’s microbiome could influence how a cancer responds to treatment.

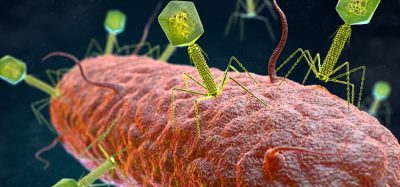

The two papers, published in Cell Reports and Nature, focused on an oral bacterium called Fusobacterium nucleatum, which has been linked to colorectal cancer. The findings also suggest a link between oral health and cancer, as microbes in the mouth are associated with cancers elsewhere in the body.

Non-cancerous cells around tumours can help it avoid attacks by the immune system, resist therapies that target them and allow it to spread to other parts of the body. Researchers are now finding that some of these cells are bacteria.

Tumour cells infected with bacteria are associated with cancer progression and metastasis. In oral tumour samples, the researchers saw that bacteria preferentially infected cancer epithelial cells and specific immune cells within patients’ tumours. Infected tumour cells had increased DNA damage signalling. These findings support bacteria having a direct role in shaping these micro-niche regions.

Combined observations from tumours with lab-based experiments and small-molecule drug screens to show that F. nucleatum may shape conditions in tumours to keep them safe from immune attack and help them spread through the body. They discovered that some cancer therapeutics may work because they not only target tumour cells, but also the bacteria that are helping them.

In the lab, the researchers grew colorectal cancer spheroids with neutrophils. The neutrophils spread through spheroids without bacteria. But in those with bacteria, neutrophils migrated to the centre of the spheroid and became trapped. This could explain why there are few T cells in regions colonized by bacteria.

Regions colonised by bacteria were highly immune suppressive and had fewer cancer-killing T cells than other areas. Areas that had T cells near bacteria also had an upregulation of immune checkpoint proteins, which restrain the cancer-killing effects of T cells. Several checkpoint inhibitors are approved for use in colorectal cancer, and this study may help explain how a patient’s microbiota could influence whether their cancer responds to a checkpoint inhibitor.

The team also found that other microbes, including E. coli may render an anti-microbicidal and chemotherapeutic drug ineffective, which could shield both the tumour and F. nucleatum from treatment. These findings could help researchers develop new strategies to treat or target cancer by tackling its microbiome.

The cancer-promoting bacterium F. nucleatum is highly sensitive to a common chemo drug: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), but the researchers found that E. coli bacteria protected colorectal cancer cells from 5-FU. E. coli apparently seemed to metabolize the drug and minimize its exposure to cancer cells or other bacteria.

“This work is at the intersection of cancer and microbiome research,” co-lead Dr Susan Bullman said. “There’s compelling emerging data to suggest that nearly all major cancer types harbour an intra-tumoural microbiota.”

Adapting a leading-edge technology that allows researchers to detect where genes are turned on and off in slices of tumour tissue, spatial transcriptomics, the team found that a range of bacterial species were living within oral and colorectal cancers, but they were not spread evenly.

“We observed bacterial hotspots, or micro-niches, which opened up a number of questions as to how these formed and might be impacting cancer biology,” Fred Hutch molecular microbiologist, Dr Christopher Johnston added.

Related topics

Drug Targets, Immuno-oncology, Immunotherapy, Microbiology, Microbiome, Oncology, T cells

Related conditions

Cancer, Colorectal cancer

Related organisations

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Centre

Related people

Dr Christopher Johnston, Dr Susan Bullman