Why do some immunotherapies fail to kill cancer?

Posted: 3 April 2023 | Izzy Wood (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Spreading cancer can halt natural pathway that should recruit killer T cells directly to where it has metastasised, US scientists report.

A new study from the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, has uncovered a strategy used by tumours that have spread, that may help explain why sometimes promising immunotherapies designed to help T cells kill cancer, fail to.

These findings, published in Cancer Cell, may also mean an additional therapeutic manoeuvre is needed to stop some tumours, which often are diagnosed after they have spread.

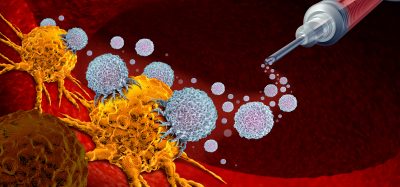

T cells are drivers of the immune response which cancer tries to waylay, and drugs like Keytruda (pembrolizumab) and OPDIVO (nivolumab), also known as immune checkpoint inhibitors, try to set these “killer” T cells free. The mutual target of cancer and these drugs is PD-1, a protein and natural checkpoint that enables T cells to be turned on or off.

The protein PD-L1 naturally binds to PD-1 to effectively turn the T cells off, which is a good thing, when helping avoid, for example, an overzealous immune response to your own body tissue which results in conditions like lupus. But cancer usurps this natural switch to protect itself in a move dubbed “immune-escape.”

“The PD-L1 cancer cells express is in direct response to the PD-1 that T cells express. One of the reasons people may not have the success you would expect with immunotherapy is the smartness of the tumor in using PD-L1.” explained Dr Kebin Liu, cancer immunologist in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Medical College of Georgia.

Cancer binds to the PD-1 on T cells, effectively turning them off. Drugs like Keytruda bind to and block the receptor for PD-1 on T cells to keep them free to attack.

Immune cells called myeloid cells talk to T cells, and can also both activate and prevent these frontline responders from attacking an invader like cancer or a virus. Myeloid cells also express PD-1.

The scientists found that metastatic tumour cells also directly engage with the PD-1 on these myeloid cells, where they suppress a natural pathway that produces type 1 interferon, which they found is essential to bringing “killer” T cells right to the spreading cancer’s doorstep.

Interferon is a natural protein made by our cells that is known to help the body fight invaders like a virus or cancer. It’s also synthetically produced to treat a variety of conditions from skin cancer to hepatitis.

“The tumour uses PD-L1 to bind to the PD-1 on the myeloid cells therefore the myeloid cells cannot produce interferon to help the T cells infiltrate the tumour,” Liu said.

They found that the signalling pathway for this interferon is essential to the recruitment of killer T cells to, in this case, the site of cancer that has spread to the lungs. They found in this scenario the PD-L1 from cancer cells interacts directly with the PD-1 on myeloid cells to suppress interferon’s production.

They already are working to see if this happens at other common sites for cancer spread like the liver. The lung and liver are usual sites of metastasis for a variety of cancers, Liu notes.

Type 1 interferon alpha was the first immunotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration and there is emerging evidence that type 1 interferon enables conversations between immune cells that are in the tumour’s supportive microenvironment.

Related topics

Immunotherapy, Oncology, Protein, T cells, Targets, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Liver cancer, Lung cancer

Related organisations

Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University

Related people

Dr Kebin Liu