Novel study suggests alternatives to aspirin with fewer side effects

Posted: 31 March 2023 | Ria Kakkad (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

The new findings could pave the way to safer aspirin alternatives and might also have implications for improving cancer immunotherapies.

New research from the University of Texas at Arlington, US, has revealed important information about how aspirin works. Even though this drug has been available commercially since the late 1800s, scientists have not yet fully elucidated its detailed mechanism of action and cellular targets. The researchers say, therefore, the new findings could pave the way to safer aspirin alternatives and might also have implications for improving cancer immunotherapies.

Aspirin, which is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, is one of the most widely used medications in the world. It is used to treat pain, fever and inflammation, and an estimated 29 million people in the US take it daily to reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

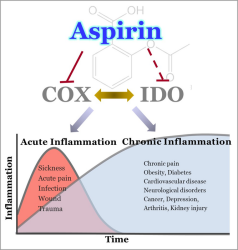

Scientists know that aspirin inhibits the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme which creates messenger molecules that are crucial in the inflammatory response. Researchers led by have discovered more about this process.

Biomarkers aren’t just supporting drug discovery – they’re driving it

FREE market report

From smarter trials to faster insights, this report unpacks the science, strategy and real-world impact behind the next generation of precision therapies.

What you’ll unlock:

- How biomarkers are guiding dose selection and early efficacy decisions in complex trials

- Why multi-omics, liquid biopsy and digital tools are redefining the discovery process

- What makes lab data regulatory-ready and why alignment matters from day one

Explore how biomarkers are shaping early drug development

Access the full report – it’s free!

“Aspirin is a magic drug, but long-term use of it can cause detrimental side effects such as internal bleeding and organ damage,” said lead scientist Professor Subhrangsu Mandal. “It is important that we understand how it works so we can develop safer drugs with fewer side effects.”

The team found that aspirin controls transcription factors required for cytokine expression during inflammation while also influencing many other inflammatory proteins and noncoding RNAs that are critically linked to inflam

Researchers have made new discoveries about aspirin’s mechanism of action and cellular targets. Their findings suggest potential interplay between cyclooxygenase enzyme, or COX, and indoleamine dioxygenases, or IDOs, during inflammation [Credit: Subhrangsu Mandal, University of Texas at Arlington].

mation and immune response. Mandal said this work has required a unique interdisciplinary team with expertise in inflammation signalling biology and organic chemistry.

They also showed that aspirin slows the breakdown of the amino acid tryptophan into its metabolite kynurenine by inhibiting associated enzymes called indoleamine dioxygenases (IDOs). Tryptophan metabolism plays a central role in the inflammation and immune response.

“We found that aspirin downregulates IDO1 expression and associated kynurenine production during inflammation,” Mandal said. “Since aspirin is a COX inhibitor, this suggests potential interplay between COX and IDO1 during inflammation.”

IDO1 is an important target for immunotherapy. As COX inhibitors modulate the COX–IDO1 axis during inflammation, the researchers predict that COX inhibitors might also be useful as drugs for immunotherapy.

Mandal and his team are now creating a series of small molecules that modulate COX–IDO1 and will explore their potential use as anti-inflammatory drugs and immunotherapeutic agents.

Prarthana Guha, a graduate student in Mandal’s lab, will present the team’s findings at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, March 25–28 in Seattle.

Related topics

Drug Development, Drug Repurposing, Immunotherapy, Molecular Biology

Related conditions

Cancer, Cardiovascular disease

Related organisations

American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Texas at Arlington

Related people

Prarthana Guha, Professor Subhrangsu Mandal