New therapeutic strategy could reduce cardiovascular disease in cancer survivors

Posted: 23 December 2022 | Izzy Wood (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

US researchers have discovered that cancer treatments or anthracycline drugs, cause cardiovascular disease by activating a key inflammatory signalling pathway.

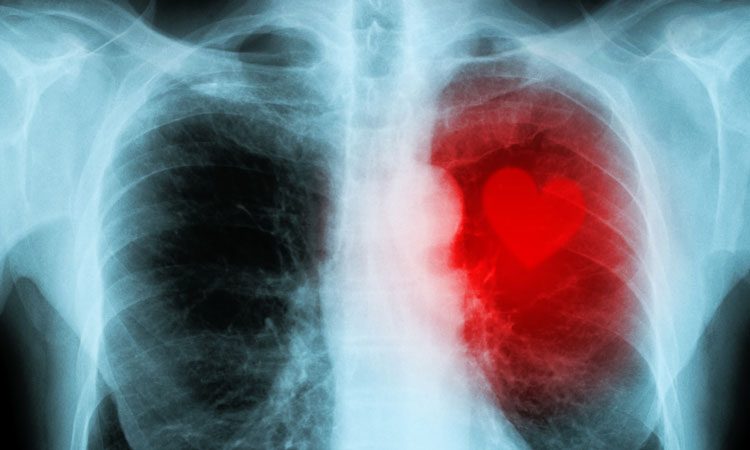

Researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC), US, have discovered that common cancer treatments, such as radiotherapy or anthracycline drugs, cause long-term damage to heart tissue (cardiovascular disease) by activating a key inflammatory signalling pathway.

The study, published in Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), suggests that inhibiting this pathway could reduce the chances of cancer survivors suffering heart disease later in life.

Radiotherapy or a class of DNA-damaging drugs known as anthracyclines can have delayed, toxic effects on the heart, increasing the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease or heart failure.

“The mechanisms by which DNA damage leads to late tissue toxicity years after cancer treatment have been poorly understood,” said Adam Schmitt, a radiation oncologist at MSKCC. “Identifying the pathogenic mechanisms of toxicity and early biomarkers of their activation would provide an opportunity to intervene with treatment to prevent toxicity.”

In their study, Schmitt and colleagues found that one month of mice being exposed to radiation or anthracyclines, a specific population of heart cells called fibroblasts activated a set of genes that promoted the recruitment of various immune cell types associated with pathological inflammation and tissue fibrosis. Within three to six months, the mice developed signs of cardiac dysfunction by 12 months, many of them had died of heart failure.

The researchers determined that this pathological process is driven by an immune signalling pathway called the cGAS–STING pathway. This pathway usually promotes inflammation in response to DNA fragments derived from pathogenic bacteria or viruses, but they reasoned it could also be activated by DNA fragments generated in response to radiation or anthracycline treatment.

Mice lacking either the cGAS or STING proteins were protected from the toxic side effects of DNA-damaging cancer treatments. They showed no signs of cardiac inflammation, maintained normal heart function, and were still alive a year after treatment. A small molecule inhibitor of the STING protein also protected mice from the toxic effects of radiotherapy or anthracyclines.

By studying breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines, the researchers found evidence that the cGAS–STING pathway may play a similarly important role in human cardiac toxicity. One of the key inflammatory proteins induced by cGAS–STING signalling is CXCL10, and the researchers found that patients who showed the largest increases in CXCL10 levels after anthracycline treatment, subsequently showed changes on echocardiograms associated with cardiac toxicity.

“Taken together, our data reveal that targeting of the cGAS–STING pathway holds great potential as a treatment to prevent cardiac complications of DNA-damaging cancer treatments,” Schmitt concluded.

“These data indicate that clinical trials utilising cGAS–STING inhibitors to prevent cardiovascular disease following DNA-damaging cancer therapy are warranted.”

Related topics

Drug Targets, Protein, Targets, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Cancer, Cardiovascular disease, Heart disease

Related organisations

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC)

Related people

Adam Schmitt