Early natural killer cells more effective than adult versions, find researchers

Posted: 24 March 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

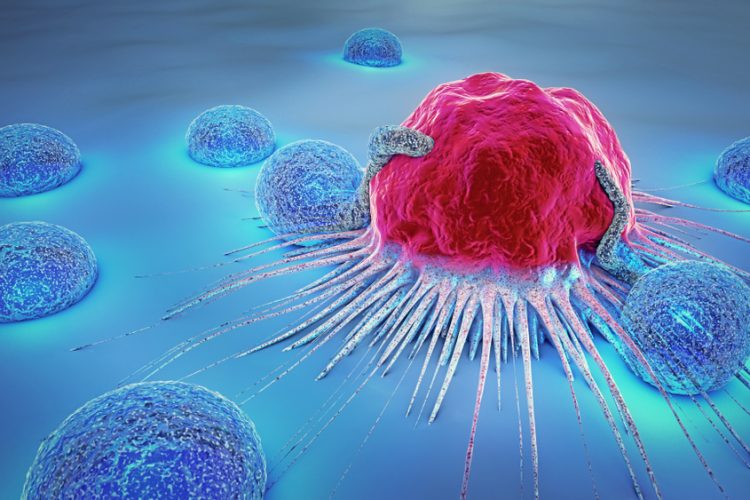

Researchers have shown that natural killer (NK) cells work best as an immunotherapy when in an early stage of development, so could be manufactured from pluripotent stem cells.

A new study has suggested that the age of certain immune cells used in immunotherapies plays a role in how effective the treatment is. According to the researchers, natural killer (NK) cells appear to be more effective the earlier they are in development, opening the door to the possibility of an immunotherapy that would be developed from existing supplies of human pluripotent stem cells.

…NK cells are better at releasing specific anti-tumour chemicals… than their adult counterparts”

“We are trying to improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy for more patients,” said senior author Dr Christopher Sturgeon, an assistant professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, US, where the study was conducted. “This special source of NK cells has the potential to fill some of the gaps remaining with adult NK cell therapy. There is early evidence that they are more consistent in their effectiveness and we would not need to process cells from a donor or the patient. They could be manufactured from existing cell supplies following the strict federal guidelines for good manufacturing practices. The characteristics of these cells let us envision a supply of them ready to pull off the shelf whenever a patient needs them.”

Unlike the adult versions of NK cells used in most investigational therapies, earlier versions of such cells do not originate from bone marrow. Instead, these NK cells are a special type of short-lived immune cell that forms in the yolk sac of the early mammalian embryo. However, for therapeutic purposes, these cells do not need to originate from embryos – they can be developed from human pluripotent stem cells. Manufacturing such cells – which the researchers say many academic medical centres already have the ability to do – would make them available quickly, eliminating the time needed to process the patient’s or donor’s cells, which can take weeks.

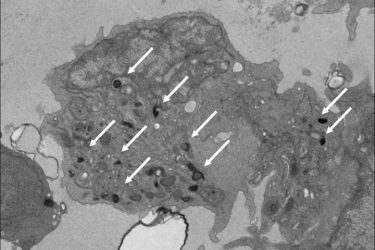

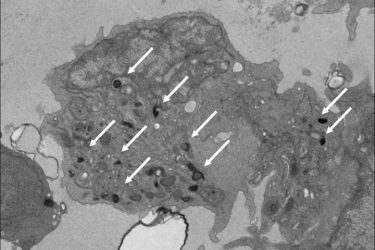

Pictured is a natural killer (NK) cell that researchers developed in the lab from human pluripotent stem cells. These NK cells mimic the properties of those found in the yolk sac during the earliest stages of development. Such NK cells may be more effective as immunotherapy for cancer treatment than adult NK cells that come from bone marrow, according to a new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis. White arrows point out granules that contain potent anti-cancer enzymes. Adult NK cells have very few of these granules [credit: Sturgeon Lab].

“Before a certain time point in early development, there is no such thing as bone marrow, but there is still blood being made in the embryo,” Sturgeon said. “It’s a transient wave of blood that the yolk sac makes to keep the embryo going until bone marrow starts to form. That’s the blood cell generation that’s making these unique NK cells. This early blood appears to be capable of things that adult blood simply cannot do.”

Studying mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that were coaxed into forming these unique NK cells, the researchers showed that the NK cells are better at releasing specific anti-tumour chemicals – a process called degranulation – than their adult counterparts. They found that even NK cells derived from umbilical cord blood do not respond as robustly.

“Now we know where these special NK cells come from and that we can never get them from an adult donor, only a pluripotent stem cell,” Sturgeon said. “Now that we know how to manufacture them and how they work, it opens the door for more trials and for improving upon their function.”

According to Sturgeon, such cells could be produced from existing lines of pluripotent stem cells that would not need to come from a matched donor because, in general, NK cells do not heavily attack the body’s healthy tissues, as many T-cell therapies can.

The study was published in Developmental Cell.

Related topics

Drug Targets, Immuno-oncology, Immuno-oncology therapeutics, Immunotherapy, Research & Development, T cells

Related organisations

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

Related people

Dr Christopher Sturgeon