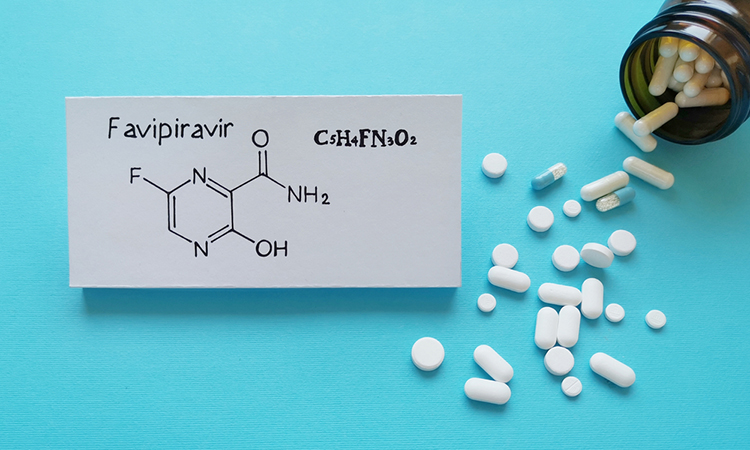

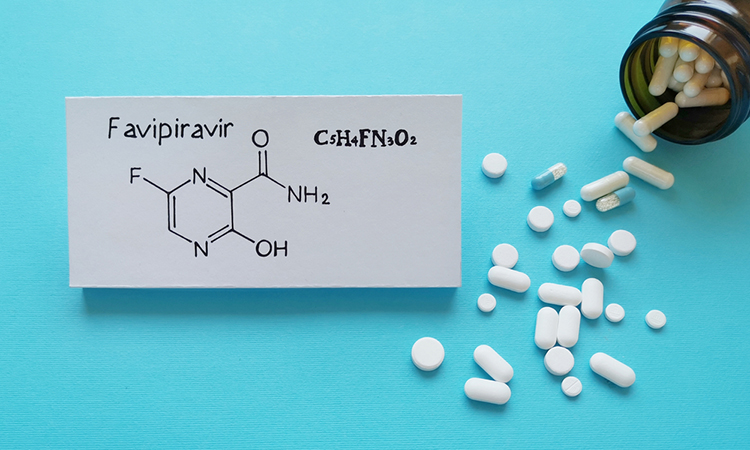

High doses of favipiravir combat SARS-CoV-2 in hamsters

Posted: 12 October 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A team showed that high doses of favipiravir can treat hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2, whereas hydroxychloroquine has no effect.

Researchers have found that a high dose of favipiravir given to hamsters has a potent combative and protective effect against SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing the COVID-19 pandemic. They also showed that hydroxychloroquine had no impact against the coronavirus.

The study was conducted at the Katholieke Universiteit (KU) Leuven Rega Institute, Belgium.

The team gave the hamsters either hydroxychloroquine or favipiravir – a broad-spectrum antiviral drug used to treat influenza – for four to five days and tested several doses of favipiravir. They then infected the hamsters with SARS-CoV-2 in two ways: by inserting a high dose of virus directly into their noses or by putting a healthy hamster in a cage with an infected hamster.

Drug treatment was started one hour before the direct infection or one day before the exposure to an infected hamster. Four days after infection or exposure, the researchers measured how much of the virus was present in the hamsters.

The researchers found that treatment with hydroxychloroquine had no effect; the virus levels did not decrease and the hamsters were still infectious.

“Based on these results and the results of other teams, we advise against further exploring the use of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment against COVID-19,” said Dr Joana Rocha-Pereira, one of the lead researchers.

A high dose of favipiravir, however, had a strong impact. A few days after the infection, the virologists detected hardly any infectious SARS-CoV-2 particles in the hamsters that received this dose and that had been infected intranasally. Moreover, hamsters that were in a cage with an infected hamster and had been given the drug did not develop an obvious infection. Those that had not received the drug all became infected after having shared a cage with an infected hamster.

However, they found that a low dose of the drug favipiravir did not have this outcome. Other lead researcher Professor Leen Delang noted: “The high dose is what makes the difference. That is important to know, because several clinical trials have already been set up to test favipiravir on humans.”

“Because we administered the drug shortly before exposing the hamsters to the virus, we could establish that the medicine can also be used prophylactically, so in prevention,” said Dr Suzanne Kaptein, another lead researcher. “If further research shows that the results are the same in humans, the drug could be used right after someone from a high-risk group has come into contact with an infected person. It may likely also be active during the early stages of the disease.”

However, the team note that general preventive use against SARS-CoV-2 is probably not an option because it is not known whether long-term use, especially at a high dose, has side effects.

Furthermore, extra research is required to determine whether humans can tolerate a high dose of favipiravir. The researchers highlight that in the past, the drug has been prescribed in high doses to Ebola patients, who appear to have tolerated it well.

The study was published in PNAS.

Related topics

Drug Repurposing, Drug Targets, In Vivo, Research & Development, Targets, Therapeutics

Related organisations

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

Related people

Dr Joana Rocha-Pereira, Dr Suzanne Kaptein, Professor Leen Delang