Antibodies cover entirety of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, study shows

Posted: 5 May 2021 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

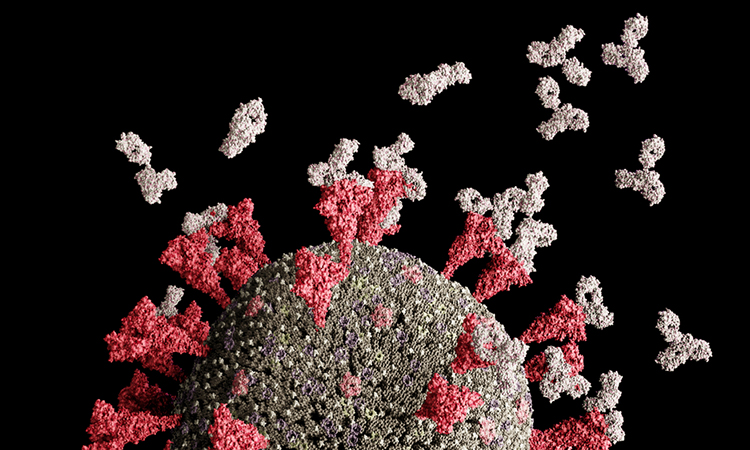

Researchers have found that over 80 percent of antibodies target sections of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein other than the RBD.

Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, US, have contributed to the developing picture of how antibodies produced in people who effectively fight off SARS-CoV-2 work to neutralise the part of the virus responsible for causing infection.

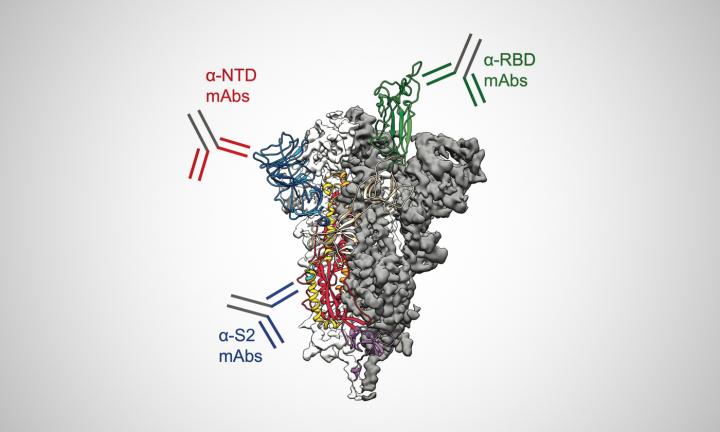

Previous research has focused on one group of antibodies that target a part of the Spike (S) protein called the receptor-binding domain (RBD). As the RBD is the part of the S protein that attaches directly to human cells and enables the virus to infect them, it was rightly assumed to be a primary target of the immune system. However, testing blood plasma samples from four people who recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infections, the researchers found that most of the antibodies circulating in the blood – on average, about 84 percent – target areas of the viral S protein outside the RBD.

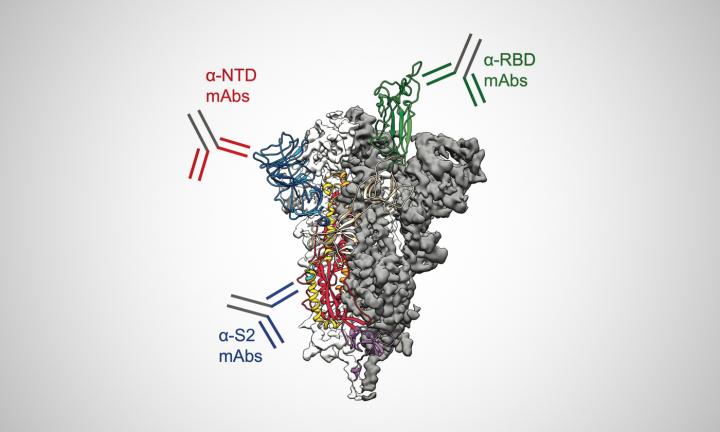

“We found these antibodies are painting the entire S, both the arc and the stalk of the S protein, which looks a bit like an umbrella,” said co-corresponding author Assistant Professor Greg Ippolito. “The immune system sees the entire S and tries to neutralise it.”

Many of these non-RBD-directed antibodies the team identified act as a potent weapon against the virus by targeting a region in a part of the S protein located in what would be the umbrella’s canopy called the N-terminal domain (NTD). These antibodies neutralise the virus in cell cultures and were shown to prevent a lethal mouse-adapted version of the virus from infecting mice.

The NTD is also a part of the viral S protein that mutates frequently, especially in several variants of concern. This suggests that one reason these variants are so effective at evading immune systems is that they can mutate around one of the most common and potent types of antibody.

An analysis of blood plasma samples from four people who recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infections shows that most of the antibodies circulating in the blood – on average, about 84 percent – target areas of the viral S protein outside the RBD [credit: University of Texas at Austin].

“There is an evolutionary arms race going on between the virus and our immune systems,” said Jason Lavinder, research associate and co-corresponding author of the new study. “We are all developing a standard immune response to this virus that includes targeting this one spot and that is exerting selective pressure on the virus. But then the virus is also exerting its evolutionary strength by trying to change around our selective immune pressures.”

Despite this, the researchers said about 40 percent of the circulating antibodies target the stalk of the S protein, called the S2 subunit, which is also a part that the virus does not seem able to change easily.

“That is reassuring,” Ippolito said. “That is an advantage our immune system has. It also means our current vaccines are eliciting antibodies targeting that S2 subunit, which are likely providing another layer of protection against the virus.”

According to the team, this is also good news for the design of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine boosters or next-generation vaccines against variants of concern and even for developing a vaccine that can protect against future pandemics from other strains of the coronavirus.

The study was published in Science.

Related topics

Antibodies, Disease Research, Immunology, Protein, Proteomics

Related conditions

Covid-19

Related organisations

University of Texas at Austin

Related people

Assistant Professor Greg Ippolito, Jason Lavinder