Study highlights possibility of using 3D organoids of the cervix to test drugs

Posted: 1 March 2022 | Ria Kakkad (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

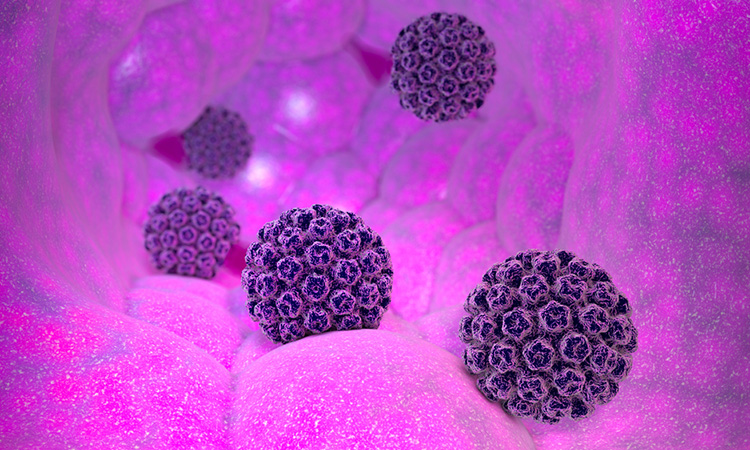

A new study modelled chlamydia and HPV co-infection in patient-derived ectocervix organoids to reveal distinct cellular reprogramming.

Researchers at the Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg (JMU), Germany have demonstrated for the first time that the human papillomavirus (HPV) works simultaneously with the bacterial pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis to “reprogramme” the cells they infect in patients with cervical cancer in such a way that they degenerate and multiply uncontrollably.

Using cells from healthy donors, they developed three-dimensional (3D) organoids of the cervix to investigate the interactions between the pathogens and tissues the disease effects and processes. The findings of this study were recently published in Nature Communications.

“Our study uses organoid models to show the danger of multiple infections. These create a unique cellular microenvironment that potentially contributes to the reprogramming of tissues and thus to the development of cancer,” said Dr Cindrilla Chumduri, head of the research group.

The research focused on two tissue types: first, the so-called ectocervix – the part of the cervical mucosa that extends into the vagina. Second is the endocervix – the part of the mucosa that lines the cervix further inside, connecting the uterus. Their essential task is to prevent pathogens from entering the uterus and thus help keep the upper female reproductive tract sterile.

Virus DNA can be found in more than 90 percent of all cervical cancers. However, they are not the sole culprit, as shown by the fact that although more than 80 percent of women become infected with HPV during their lifetime, not even two percent develop cancer. Coinfection with Chlamydia trachomatis is therefore thought to be a major cofactor in driving malignant tissue formation. However, “the dynamics of this coinfection and the underlying mechanisms have been largely unknown,” added Dr Rajendra Kumar Gurumurthy, co-first author of the study.

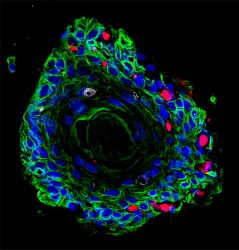

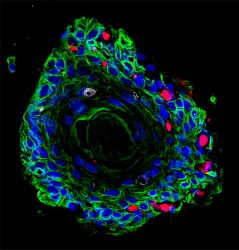

Image of patient-derived ectocervical stratified squamous organoids (green) infected with Chlamydia trachomatis (red).

[Credit: Team Chumduri].

“Unlike tumour viruses, whose DNA can be found in tumours, bacteria associated with cancer rarely leave detectable elements in cancer cells,” explained Chumduri. Nevertheless, to link bacteria to cancer development, she said, it is necessary to identify those cellular and mutational processes that contribute to cells undergoing pathological changes. Chumduri and her team have now systematically precisely decoded these processes in the organoids they have developed.

The results of this study showed that HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis cause unique cellular reprogramming of the host. Several genes were either up-or down-regulated by the two pathogens in different ways, which is associated with specific immune responses. Among other things, pathogens influenced a significant subset of all regulated genes responsible for DNA damage repair. Therefore, the researchers concluded, co-persistence of HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis in a stem cell could adversely affect cellular and genomic stability and promote neoplastic progression.

The study also provided the first evidence that the 3D organoids of the cervix are suitable for studying various aspects of cervical biology, including drug testing under near-physiological conditions. The cultivability of these organoids and the possibility of genetically manipulating them thus open new avenues to study the development, progression and outcome of chronic infections in an authentic pre-clinical setting.

Related topics

Cell Regeneration, DNA, Organoids, Technology, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Cervical cancer, Chlamydia trachomatis, HPV

Related organisations

Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg (JMU)

Related people

Dr Cindrilla Chumduri, Dr Rajendra Kumar Gurumurthy