Study finds coronaviruses do not readily induce cross-protective antibody responses

Posted: 19 May 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have found that antibodies produced in response to SARS and COVID-19 are cross-reactive, but not cross protective in cells and mice.

According to a new study, patients infected with either severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) or SARS-CoV-2, which is causing the COVID-19 pandemic, produce antibodies that bind to the other coronavirus, but the cross-reactive antibodies are not cross protective in cell-culture experiments.

The researchers say it remains unclear whether such antibodies offer cross protection in the human body or potentiate disease and that the findings suggest more research is needed to identify parts of the virus that are critical for inducing a cross-protective immune response.

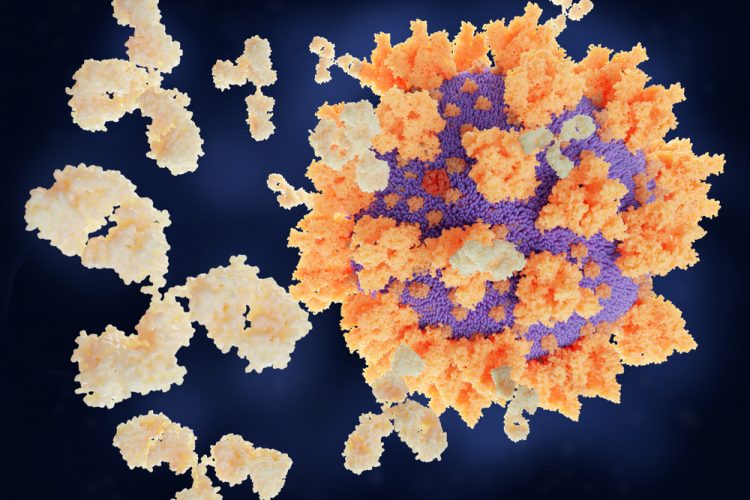

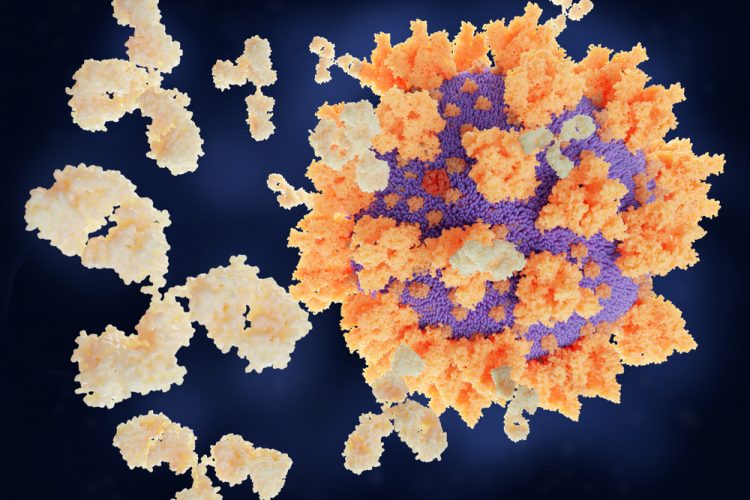

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus, known as SARS-CoV, shares approximately 80 percent of its genomic nucleotide sequence identity with that of SARS-CoV-2. The two coronaviruses also enter and infect cells the same way. During this process, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the Spike (S) protein, which is located on the surface of the coronavirus, binds to a human cell receptor called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), triggering viral fusion with the host cell.

“Our findings, albeit limited at present, would suggest that broadly cross-neutralising antibodies to coronaviruses might not be commonly produced by the human immune repertoire. Moving forward, monoclonal antibody (mAb) discovery and characterisation will be crucial to the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the short-term, as well as a cross-protective coronavirus vaccine in the long term,” said co-senior study author Chris Mok of the University of Hong Kong.

Past studies have shown that protective antibodies against SARS-CoV bind to the RBD. However, relatively little is known about the antibody response induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is also unclear how infection with SARS-CoV influences the antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 and vice versa. Therefore, the researchers say that gaining insight into these questions could guide the development of an effective vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 and shed light on whether such a vaccine would also cross-protect against similar viruses.

“There are related viruses still circulating in bats and it is unclear whether any of these may also threaten human health in future,” said co-senior study author Malik Peiris of the University of Hong Kong. “As such, whether infection by one of these viruses cross-protects against another is an important question.”

The team analysed blood samples collected from 15 SARS-CoV-2-infected patients in Hong Kong between two and 22 days after the onset of symptoms. Compared to blood samples from healthy controls, the five samples collected from patients 11 days after symptom onset or later had antibodies capable of binding to the RBD and other parts of the S protein on both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV.

The researchers also analysed blood samples collected from seven patients three to six months after infection with SARS-CoV. Compared to blood samples from healthy controls, those collected from patients had antibodies capable of binding to the RBD and other parts of the S protein on SARS-CoV-2. Taken together, these findings show that infection with one coronavirus induces the production of antibodies that can bind to both RBD and non-RBD regions of the S protein on the other coronavirus.

Using cell-culture experiments, the researchers tested whether infection with SARS-CoV-2 induces SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralising antibodies, which protect host cells by preventing the virus from interacting with them. All 11 blood samples collected 12 days or later after the onset of symptoms had neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. However, only one blood sample had cross-neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV and this response was very weak. Similarly, five blood samples from patients infected with SARS-CoV had neutralising antibodies against this virus, but none could cross-neutralise SARS-CoV-2. Additional experiments in mice supported the findings from patients.

For now, the researchers say the clinical implications remain unclear. One possibility is that cross-reactive, non-neutralising antibodies offer cross protection against viruses in the body, even though they do not protect cultured cells. On the other hand, non-neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 could enhance viral entry into cells and viral replication through a process called antibody-dependent enhancement of infection, which has been previously reported for SARS-CoV.

“Whether antibody-dependent enhancement plays a role in SARS-CoV-2 infection needs to be carefully examined in the future,” said co-senior study author Ian Wilson of the Scripps Research Institute. “Addressing this question will be critical for developing a safe and effective universal coronavirus vaccine.”

The study was published in Cell Reports.

Related topics

Antibodies, Antibody Discovery, Disease Research, Drug Targets, Immunology, Research & Development

Related conditions

Coronavirus, Covid-19, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Related organisations

The Scripps Research Institute, University of Hong Kong

Related people

Chris Mok, Ian Wilson, Malik Peiris