Milestone reached in search of vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus

Posted: 14 March 2022 | Ria Kakkad (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A new study has showed how a bioengineered RSV protein vaccine can induce a protective immune response in animal models.

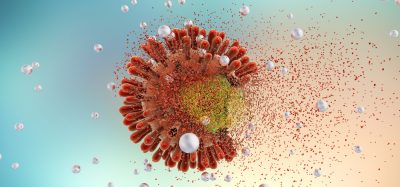

Researchers from the University of California, US have published their new findings in their pursuit of finding a vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a common and sometimes dangerous respiratory disease. The team have recently focused on bioengineering the structure of RSV’s G protein, which attaches the virus to host cells. They altered the structure of the protein to eliminate its negative effects, while still eliciting a protective response from the immune system in the form of antibodies that bind to the G protein.

The team’s earlier research showed that their engineered G protein was able to stimulate a stronger antibody response than the native G protein. However, it was unclear if the engineered G protein still looked like the native protein does on the surface of the virus. The newest study, published in Journal of Virology, confirms that this engineered G protein looks the same and is recognised by human RSV-fighting antibodies.

“My paper shows that the engineered mutation in the protein does not disrupt the ability of antibodies to bind it, so when it is used as a vaccine antigen it is possible to elicit these protective antibodies in animal models and hopefully in the future people will be protected from the disease,” said lead author, Ana Nuñez Castrejon.

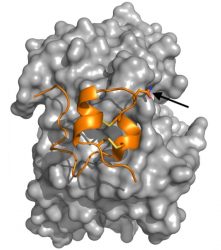

The engineered RSV G protein, with the RSV G antigen in orange and the human antibody in grey. The arrow points to the place where the researchers engineered the antigen, doing so while not affecting its ability to bind to the antibody.

[Credit: Rebecca DuBois].

The paper used structural biology to ensure that an engineered version of a virus could be recognised by the immune system to fight the actual virus.

“I think what people are coming to realise is that we can make vaccines that stimulate immune responses that are better than you get from infection, if we can engineer the antigens in a way that really exposes the weaknesses of the virus,” said Associate Professor of Biomolecular Engineering, Rebecca DuBois.

The researchers how to further analyse their results in collaboration with the University of Georgia as to how their engineered protein affected disease symptoms in mice and will continue to engineer the RSV G protein to produce stronger immune responses. In the next five years, they hope to develop an RSV vaccine using their engineered protein that is ready for clinical trials.

Related topics

Antibodies, Antibody Discovery, Drug Development, Drug Discovery, Drug Discovery Processes, In Vivo, Vaccine

Related conditions

respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Related organisations

California University

Related people

Ana Nuñez Castrejon, Rebecca DuBois