Vaccine to potentially protect against disfiguring skin disease developed

Posted: 21 March 2022 | Ria Kakkad (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

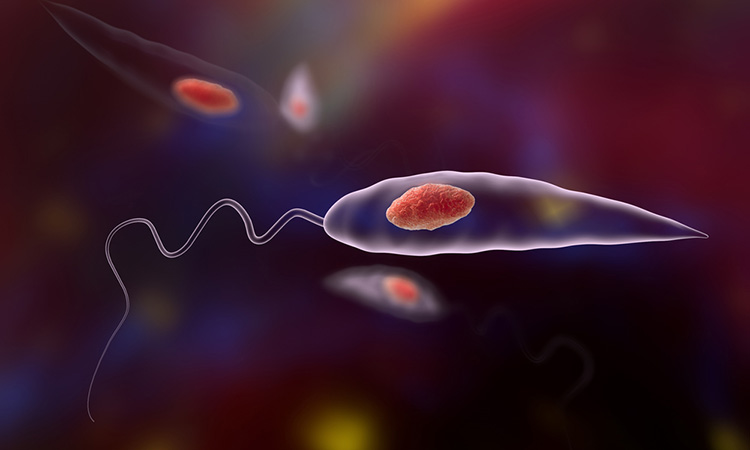

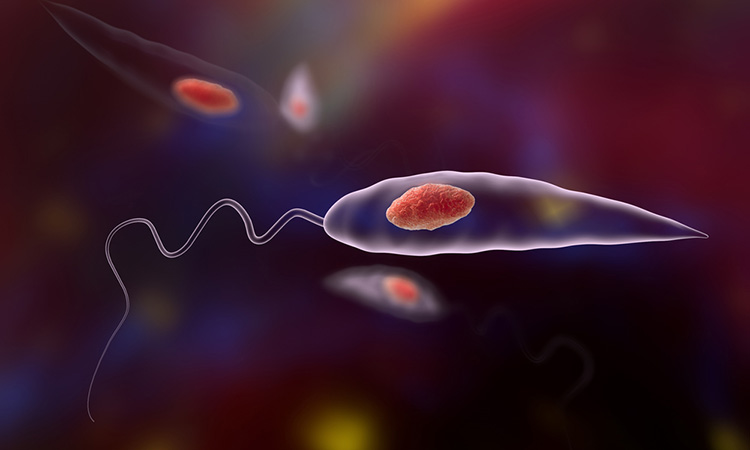

Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, scientists have developed a vaccine designed to prevent infection by Leishmania major.

Researchers at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, US have used CRISPR gene-editing technology to create a vaccine against Leishmania mexicana (L. mexicana), a parasite species that is found in South, Central and North America. The researchers have already developed a vaccine against Leishmania major (L. major), for which Phase I human trials are set to start later this year. However, L. mexicana causes a more chronic infection that, unlike skin lesions generated by L. major infection, will not self-heal. Researchers expect the L. major mutant parasite vaccine to be effective against the L. mexicana species but have developed the second vaccine as a back-up. Their technique could also tame the more virulent organism.

In both vaccines, the team applied gene-editing technology to the century-old Middle Eastern practice of leishmanisation, deliberately introducing the live parasite to the skin to create a small infection that, once healed, leads to life-long immunity against further disease.

Using the precision technology to edit the genome of L. mexicana, researchers deleted centrin. This gene codes for a protein that supports cell division and inactivated an antibiotic resistance marker gene is introduced into the parasite as part of deleting centrin.

Under normal conditions, these parasites cause infection by hijacking immune cells and use host cells to replicate indefinitely. However, experiments in immune cell cultures showed that the mutant parasite could enter cells and make limited copies of itself, but not enough to cause symptoms.

The study, which was published in npj Vaccines, showed in mice that the vaccine is safe, causing no skin lesions in animals that are susceptible to the disease. In further experiments, researchers vaccinated mice and exposed them six weeks later to the L. mexicana parasite with a needle challenge to the ear, a technique used to mimic a sand fly bite. In humans and animals, leishmania is transmitted through the bite of infected sand flies.

Unlike the unvaccinated control group, vaccinated mice remained clear of skin lesions and the number of parasites at the infection site was held at bay and the protection was sustained over 10 weeks.

Researchers are pursuing vaccines to provide an affordable way to prevent a disease that can lead to disfigurement, disability, social stigma and poverty. The team estimates that a vaccine would likely cost less than $5, compared to the $100 to $200 cost for treatment in the hardest-hit countries – treatment that requires weeks of daily drug injections with unpleasant side effects, leading to poor patient compliance that allows parasites to develop resistance to the drugs.

Visceral leishmaniasis affects organs and is fatal if left untreated. While the L. major vaccine may also prevent this more severe form of the disease, the team has used the CRISPR technique to work on a vaccine with the Leishmania donovani parasite that causes visceral leishmaniasis.

Related topics

CRISPR, Drug Delivery, Drug Development, Drug Discovery, Drug Discovery Processes, Drug Leads, Drug Targets, Gene Testing, Gene Therapy, Genome Editing, In Vivo, Research & Development, Vaccine

Related conditions

Leishmania

Related organisations

The Ohio State University College of Medicine