Parkinson’s: new study rethinks dopamine’s role in movement

Posted: 18 December 2025 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

A new study is challenging long-held beliefs about dopamine’s role in movement, revealing new insights into how Parkinson’s disease treatments work and pointing towards more targeted future therapies.

A study led by McGill University is challenging a widely accepted theory about how dopamine controls movement, a discovery that could reshape scientific thinking around treatments for Parkinson’s disease.

The research suggests that dopamine does not directly determine the speed or force of individual movements, as previously believed. Instead, it appears to play a more central role, acting as a supportive system that allows movement to occur at all.

The findings question years of assumptions about how the brain regulates motor control and may help explain why existing Parkinson’s treatments are effective, while pointing towards more targeted therapies in the future.

Automation now plays a central role in discovery. From self-driving laboratories to real-time bioprocessing

This report explores how data-driven systems improve reproducibility, speed decisions and make scale achievable across research and development.

Inside the report:

- Advance discovery through miniaturised, high-throughput and animal-free systems

- Integrate AI, robotics and analytics to speed decision-making

- Streamline cell therapy and bioprocess QC for scale and compliance

- And more!

This report unlocks perspectives that show how automation is changing the scale and quality of discovery. The result is faster insight, stronger data and better science – access your free copy today

Rethinking dopamine’s role

For decades, dopamine has been associated with motor vigour – the capacity to move quickly and with strength. In people with Parkinson’s disease, the gradual loss of dopamine-producing neurons leads to hallmark symptoms such as slowness of movement, tremors and difficulties with balance.

In people with Parkinson’s disease, the gradual loss of dopamine-producing neurons leads to hallmark symptoms such as slowness of movement, tremors and difficulties with balance.

The dominant theory held that rapid bursts of dopamine during movement acted like a control dial, directly setting how fast or forcefully a person moves. However, the new study presents a different explanation.

“Our findings suggest we should rethink dopamine’s role in movement,” said senior author Nicolas Tritsch, assistant professor in McGill’s department of psychiatry and researcher at the Douglas Research Centre. “Restoring dopamine to a normal level may be enough to improve movement. That could simplify how we think about Parkinson’s treatment.”

Why levodopa works

Levodopa has long been the standard treatment for Parkinson’s disease, helping to alleviate motor symptoms by increasing dopamine levels in the brain. Despite its widespread use, scientists have not fully understood why it is so effective.

In recent years, advances in neuroscience allowed researchers to detect rapid dopamine spikes during movement. These observations reinforced the idea that such bursts were responsible for controlling movement vigour.

The McGill-led study, however, suggests that this interpretation may be incorrect.

“Rather than acting as a throttle that sets movement speed, dopamine appears to function more like engine oil. It’s essential for the system to run, but not the signal that determines how fast each action is executed,” said Tritsch.

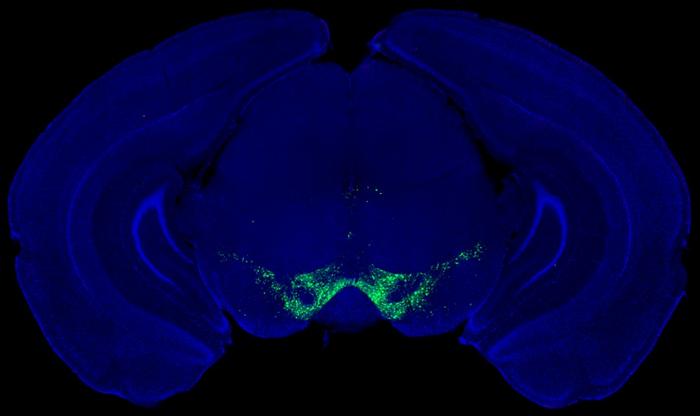

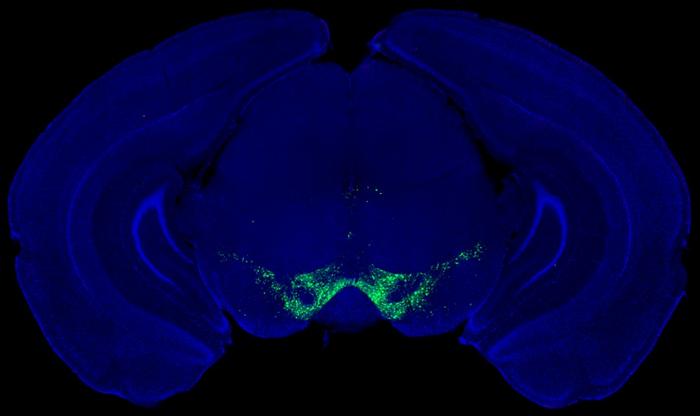

Fluorescence microscopy image of dopamine-producing neurons (green) in the midbrain of a mouse. Credit: Nicolas Tritsch.

Measuring dopamine in real time

To test their hypothesis, the researchers measured brain activity in mice as the animals pressed a weighted lever. Using a light-based technique, they were able to switch dopamine-producing cells on or off at precise moments during movement.

To test their hypothesis, the researchers measured brain activity in mice as the animals pressed a weighted lever.

If fast dopamine bursts were responsible for controlling vigour, altering dopamine levels at those moments should have changed how quickly or forcefully the mice moved. Instead, the researchers found no effect.

Further experiments with levodopa revealed that the drug works by raising the brain’s baseline level of dopamine, rather than by restoring fast dopamine spikes.

Implications for future treatments

By understanding how dopamine supports movement, the study offers a clearer explanation for why levodopa is effective and could help to inform new treatments aimed specifically at maintaining healthy baseline dopamine levels.

The findings may also prompt renewed interest in older therapies, such as dopamine receptor agonists. While these drugs have shown promise, they have often caused significant side effects because they act too broadly across the brain. A better understanding of dopamine’s true role could help scientists design safer, more precise versions in the future.

Related topics

Animal Models, Central Nervous System (CNS), Disease Research, Drug Discovery Processes, Drug Targets, In Vivo, Neurons, Neurosciences, Pharmacology, Therapeutics, Translational Science

Related conditions

Parkinson's disease

Related organisations

McGill University