Epigenome editing used to reverse gene mutation in mice

Posted: 11 December 2019 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A study has demonstrated the success of changing the genome of mice, regulating the production of the C11orf46 gene.

Using a targeted epigenome editing approach, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine, US have reversed a gene mutation that leads to the WAGR genetic disorder in humans, in developing mouse brains.

The editing was unique in that it changed the epigenome without changing the actual genetic code of the C11orf46 gene.

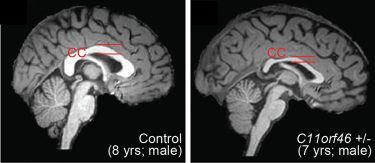

Healthy human brain (left) and brain with WAGR syndrome, in which the corpus callosum is thinner and misformed (credit: Nature Communications).

This gene is important during brain development, regulating the direction-sensing proteins that help to guide the long fibres growing out of newly formed neurons responsible for sending electrical messages, helping them to form into a bundle and connecting the two hemispheres of the brain.

Failure to properly form this bundled structure, known as the corpus callosum, can lead to conditions such as intellectual disability, autism or other brain development disorders.

The researchers used a genetic tool, short hairpin RNA, to cause less of the C11orf46 protein to be made in the brains of mice. The fibres of the neurons in the mouse brains with less of the C11orf46 protein failed to form the corpus callosum.

The gene that makes Semaphorin 6a, a direction-sensing protein, was turned on higher in mice with lower C11orf46. By using a modified CRISPR genome editing system, the researchers were able to edit a portion of the regulatory region of the gene for Semaphorin. This editing of the epigenome allowed C11orf46 to bind and turn down the gene in the brains of these mice, which then restored the neuron fibre bundling to that found in normal brains.

“Although this work is early, these findings suggest that we may be able to develop future epigenome editing therapies that could help reshape the neural connections in the brain and perhaps prevent developmental disorders of the brain from occurring,” says Dr Atsushi Kamiya, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The study was published in Nature Communications.

Related topics

Epigenetics, Genome Editing, Genomics, Protein, Research & Development

Related conditions

WAGR genetic disorder

Related organisations

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Related people

Dr Atsushi Kamiya